1998 Is Whispering

US interest rate policy is no longer on a preset path. Neither are bonds.

The minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) latest meeting arrived with their usual three-week delay. Such documents rarely change the story. This time, they may have.

Chair Jerome Powell’s press conference on January 28 left investors searching for clarity on what, precisely, would justify further easing. The minutes suggest the answer is straightforward, if not especially comforting for those hoping for imminent cuts. Inflation remains the dominant concern, and most participants indicated they would need to see additional evidence of progress before considering any reduction in rates. That’s a process that could take some time.

Markets had already begun to edge toward the conclusion that policy would remain on hold through much of the first half of the year. The minutes reinforce that view.

More interestingly, they reopened a possibility investors had largely set aside. Several participants noted that the Committee’s policy outlook might better be described as “two-sided,” explicitly acknowledging that further increases in interest rates could be appropriate should inflation remain above target.

The Fed is not signalling that it intends to hike. But it is reminding markets that it has not ruled the option out.

A Historical Lookback

Before we take a look forward at the current outlook for inflation, labour, and demand for US Treasuries, it may first be worth looking back.

The closest modern parallel to a Fed contemplating both easing and renewed tightening came not in the inflationary 1970s, but during the tenure of Alan Greenspan.

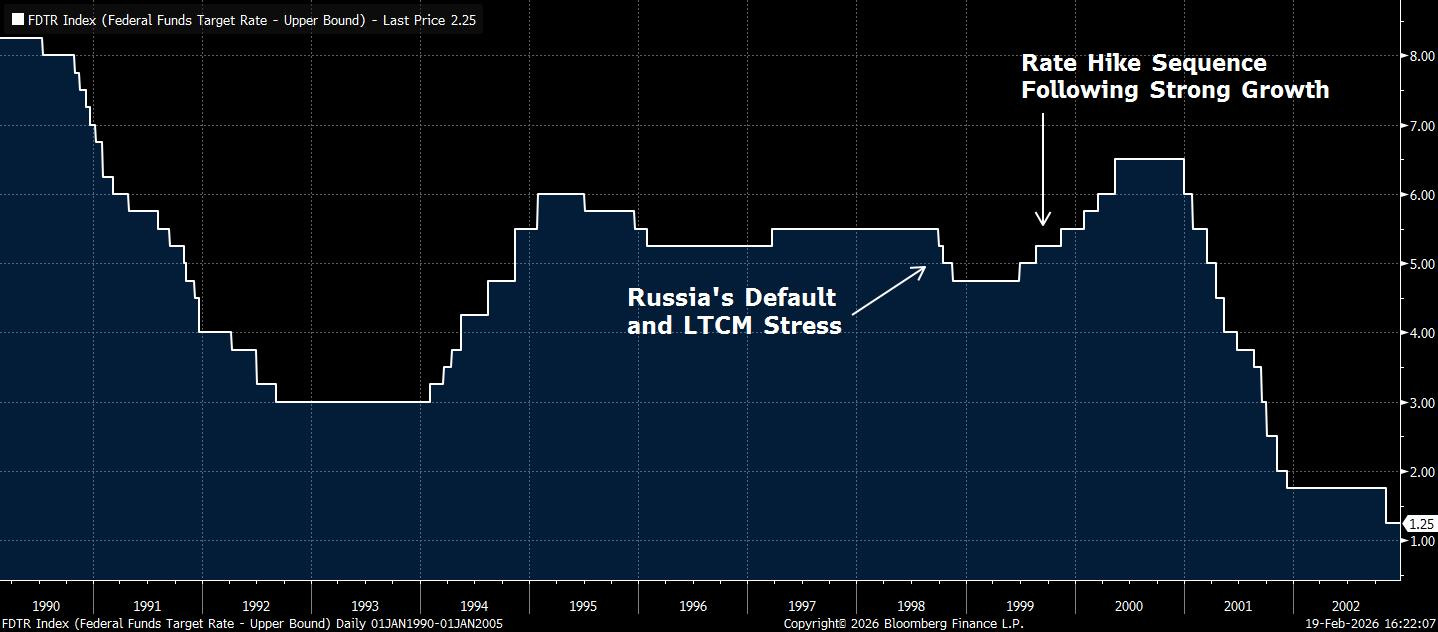

In the autumn of 1998, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates three times in quick succession. The motivation was less so domestic weakness—the US economy was expanding at a healthy pace. Instead, policymakers were responding to a sudden tightening in global financial conditions following Russia’s default and the near-collapse of Long-Term Capital Management. The cuts were framed explicitly as insurance against systemic stress.

The modern-day comparison could be argued to be Powell’s comments about not falling behind the labour market in the second half of last year.

Those cuts in 1998 worked, perhaps too well. Financial markets stabilised rapidly. Credit spreads retraced. Equity markets surged to new highs. Rather than slowing, US growth accelerated into what would become the final phase of the technology boom.

By mid-1999, the rationale for emergency accommodation had evaporated. Inflation pressures were beginning to build, not because of supply shocks, but because an already-strong economy had been given additional stimulus. The Fed reversed course, beginning a sequence of rate increases that continued into 2000.

What is striking in retrospect is how little the underlying economy changed between the easing and the subsequent tightening. The shift lay instead in the balance of risks as perceived by policymakers. Insurance cuts designed to guard against downside tail risks ended up adding fuel to an expansion that required restraint.

The modern-day similarity can be linked to the debate over whether AI will increase the need to cut or hike. Incoming Chair Warsh is on the former side of that debate. In recent days, Barr and Jefferson have made the opposite argument.

“AI will be a significant disinflationary force, increasing productivity and bolstering American competitiveness.” — Fed Chair nominee Kevin Warsh

“I expect that the AI boom is unlikely to be a reason for lowering policy rates.” — Fed Governor Michael Barr

“All other things being equal, persistent increases in productivity growth are likely to result in an increase in the neutral rate, at least temporarily.”

— Fed Vice Chair Philip Jefferson

The comparison of today against the late 1990s is not exact. We acknowledge that. Today’s Fed faces an inflation problem that Greenspan largely did not. But the structure of the policy dilemma is similar.

The initial move toward easier policy has been justified as calibration rather than crisis response.

Growth has remained resilient.

Financial conditions have eased more than expected.

Inflation progress has proven uneven.

In that environment, policy can migrate from a one-directional debate about when to cut, to a two-sided discussion about whether current settings are restrictive enough. This week’s FOMC minutes present as Exhibit A.

Validating the Fed’s View on Labour and Inflation Since Its Meeting

Before we touch on the US curve’s recent flattening and ideas in the rates space, let’s first validate the Fed’s views, factoring in the data prints since that meeting on January 27-28.

One immediate objection is that the minutes may already be out of date. Economic data released since the meeting offer ammunition to both sides of the policy debate, and if anything have made the picture less clear.