Part of the content that we put out at AP is designed to be educational. Yet we feel there’s also an area where things can be both educational and interesting. The bulk of our readership base is related to global markets in some form but at varying degrees of expertise.

We started a primer series last year for a variety of different financial instruments based on our experience of trading the products. We’ll point out the common mistakes as well as the little wrinkles to make note of, all of which we hope will make users more informed and close the knowledge gap in areas where information isn’t that readily available.

Today, we want to break down the Option Greeks, explaining how each works, which ones are relevant, how to interpret the figures and most importantly - how to use them to enhance decision-making.

Let’s get into it.

What Are The Option Greeks?

Option Greeks are financial metrics that measure the sensitivity of an option's price to various factors. As such, they are key for anyone who is trading options.

An option is a financial derivative that conveys the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specified price on or before a specified date.

We’re guessing that if you’re interested in option Greeks, you’ve got a decent base-level knowledge of options in general.

The main Greeks to be aware of are delta, gamma and theta. There are technically a host of other Greeks out there, but they are more for the CFA textbook and aren’t really massively applicable for those using options ‘on the ground’.

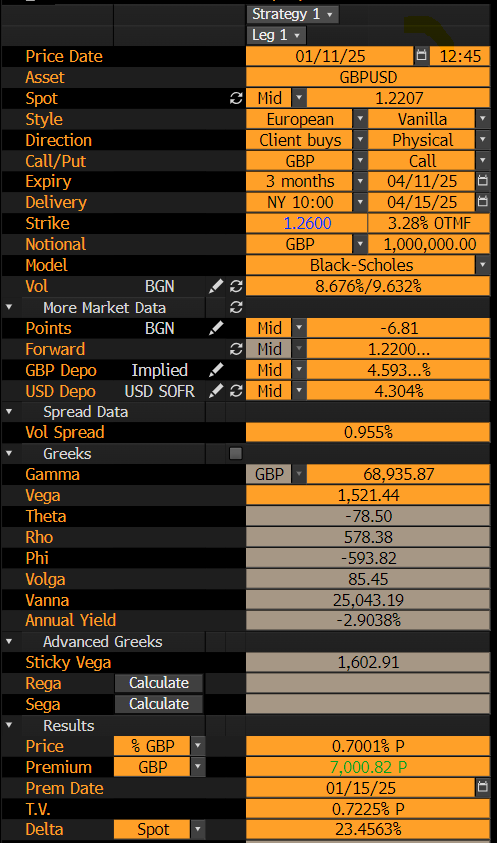

For each of the Greeks, we’re going to explain them using a priced-up trade, namely a GBP/USD vanilla call option with a 3-month tenor, spot at 1.2207 and the strike OTM at 1.2600.

Delta

Delta (Δ) is a measure of an option's price sensitivity to changes in the price of the underlying asset. It’s a number that ranges from -1 to +1, with heavy ITM options being closer to -1/+1, ATM options being -/+0.5, and really OTM options having a delta close to 0.

An alternative way of looking at delta is that it can be interpreted as the approximate probability that the option will expire in-the-money (ITM). In reality, this is the main point we use delta for when initially looking at an option pricing.

For example, let’s look at the delta of our GBP/USD option (bottom line):

The second line from the bottom shows the delta at 23.45%. You can convert this from a percentage if you want and look at it as 0.2345 (when using our initial 0-1 banding). So here, the probability that this OTM Call finishes above 1.2600 is just over 23%.

If you wanted, you can specify the option strike based on a desired delta. For example, if you wanted this trade to have a delta of 0.40 / 40%, you could input this, in which case your strike increases to 1.2332. Logically, this makes sense; you’re increasing the likelihood of the option finishes in profit, so the strike is going to be lower than the initial 1.2600.

Why Important

One reason why the delta of a trade is so important is that some traders always target specific strike prices when buying or selling. Let’s be honest: buying an option with a delta of 0 or 100 isn’t going to give you the payoff profile you want in order to generate money in 99% of circumstances.

Therefore, targeting delta in the region of 0.25-0.45 is often seen as the best area. You’re buying/selling OTM strikes, but not a huge way away from the spot price. The probability of it going ITM is reasonable, with better risk/reward parameters.

Now let’s go back to the sign in front of the number that we spoke of to begin with. This is noteworthy as call options have a positive delta of 0-1, whereas put options have a negative delta of 0 to -1.

This is because the delta is the expected change in the option’s price for a one unit change in the price of the underlying asset. So if GBP/USD spot falls, the put options gains. If spot rises, the put value falls. The inverse relationship is why the put delta is negative.

Delta Hedging

Some think that delta hedging is just used by the options desks at large institutions. This isn’t the case, and indeed anyone, even if they just hold one outstanding option position, can make themselves delta neutral (i.e having a delta of zero).

Why would you want to become delta-neutral? Well, if you’re holding a position over a data release, central bank meeting or another event whereby the spot is likely to move, but you don’t want to take on the risk for this event, you could hedge your delta. It would mean that you aren’t exposed to the option price sensitivity to changes in the price of the underlying asset (which is what delta is…)

After things have settled down, you can then remove your hedge if you want.

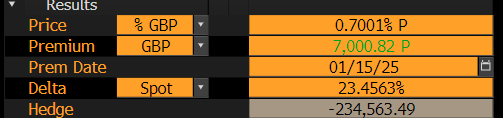

So let’s say that we bought out GBP/USD option for £1m notional with a delta of POSITIVE 0.23 but wanted to immediately make ourselves delta neutral to bring it down to zero. The ‘hedge’ value shown below gives us the clue:

It gives us a NEGATIVE hedge position of £234k. This should look familiar, given that it’s the same percentage as the delta above it, just converted based on our notional amount. It means that we would sell £234k of the underlying (i.e. a spot trade selling GBP buying USD), which would make us delta-neutral.

Think about it - we’ve bought an option that appreciates in value if GBP gains vs USD. The delta will also increase if the spot moves higher. To ‘hedge’ ourselves against this ‘risk’, we sell GBP at spot, gaining if GBP falls in value vs USD. This gain at spot is needed for the loss in value of the option in this scenario.

The delta is constantly changing, so to be perfectly neutral all the time isn’t that plausible as a retail trader.

Factors Impacting Delta

We’ve mentioned that if the underlying moves more ITM, the delta will increase. Another factor is that as we approach expiration, ITM options will move towards 1, while OTM moves towards 0.

Higher volatility can cause deltas of ATM options to stabilise closer to 0.5 (as the probability distribution of prices widens).

Delta Neutral Structures

Some traders don’t want to be exposed to delta at all. They might reason that they aren’t wanting to bet on a directional movement in the spot rate but rather on another factor, such as volatility.

If a trader wants to bet that GBP/USD will become more volatile over the next three months but doesn’t want to be exposed to delta, they can buy delta-neutral ideas.

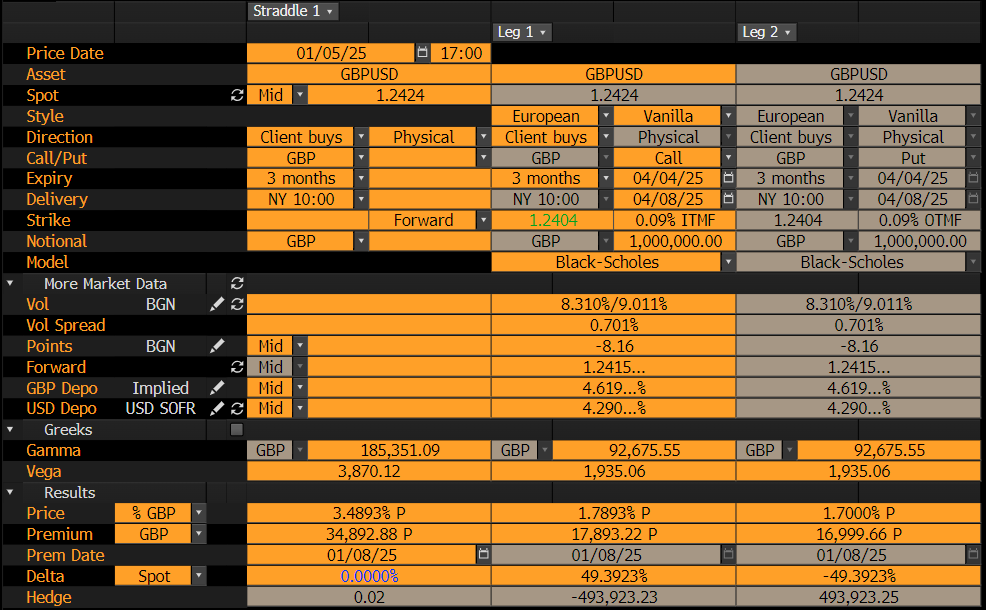

For example, look at the straddle below:

In this case, we’ve bought a 1.2404 strike call and a 1.2404 strike put option. The delta is almost 0.5 for the call and -0.5 on the put. So, our net delta is 0. The trader wouldn’t be negatively impacted by spot moving in one direction. Rather, if it was a volatile move (in either direction), the trade would be profitable.

Gamma

Gamma (Γ) is one step further on from delta. Specifically, it measures the rate of change of an option’s delta with respect to changes in the price of the underlying asset.

The first thing to note is that gamma is always positive for both call and put options, as delta increases for calls and decreases for puts as the underlying price moves closer to the strike price.

Let’s go back to our GBP/USD 1.2600 strike Call, with the notional of £1m and the initial delta of £234k. Below, you can see on the top line the gamma exposure:

So, our initial gamma for this OTM strike option is circa £69k. This means that if spot moves 1% higher, the rate of change of our delta would amount to £69k. Put another way, if spot jumped by 1%, we’d need to sell another £69k in order to keep ourselves delta-neutral.

Why Important

Your gamma will be highest at ATM strikes, as the delta is most sensitive to sharp changes as an option moves from either ATM to ITM or ATM to OTM. So, if you are delta hedging, you need to be a lot more active with ATM strikes, as your gamma is going to be high.

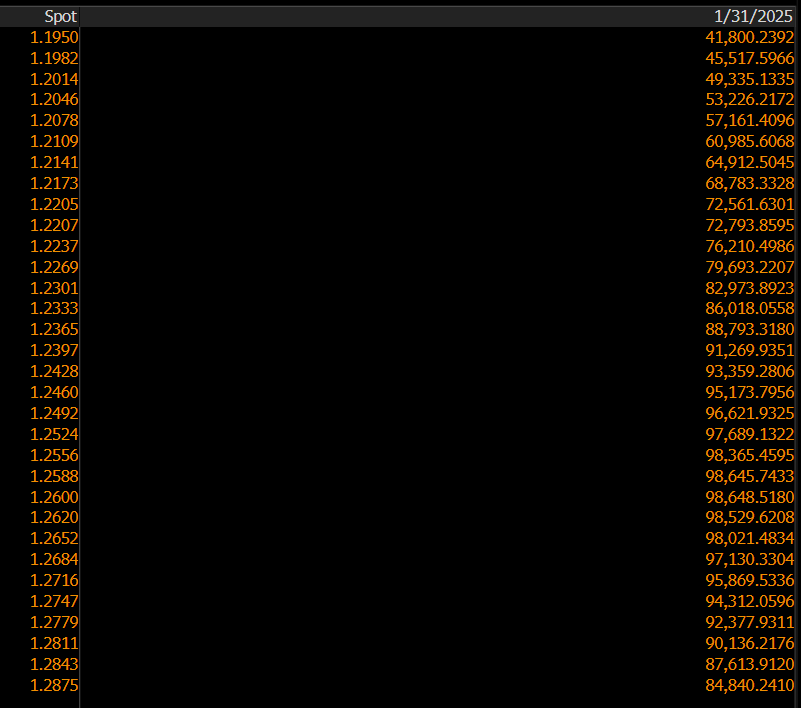

Look at the gamma exposure versus spot movements in GBP/USD based on where spot could be at the end of this month:

You’ll note that the gamma is highest if spot was at 1.2600, i.e. ATM. It tails off as the option goes more ITM or OTM.

For heavily OTM or ITM options, gamma is virtually zero. For example, if you changed your strike on GBP/USD to 1.40, you have a delta of zero. Yet even if spot moves a cent higher, the delta is likely to remain zero, given how OTM the strike is. The gamma (the change from 0 to 0) is also zero.

This comes into play primarily when you are delta hedging for risk management. High gamma can lead to significant changes in delta, increasing the risk of large portfolio swings (again with reference to ATM strikes). Understanding gamma allows a trader to better manage their book overall.

Gamma Implications

Another reason to understand gamma relates to the impact it has on the market in general. You might have heard comments such as “the market is long gamma”. Let’s break it down.

If you own options (either calls or puts), you’re long/positive gamma. For example, with our call option, it the market rises, our delta will increase and we will always have a positive gamma figure. This means that we want the market to continue to trend higher.

If you were long a put, your gamma is still positive, and you want the market to continue to trend lower.

On the flipside, if you are selling puts and calls, you’re short gamma. Ideally, you want the opposite to happen; you want the market to not move and just revert back to where it started. This allows you to keep the premium that someone paid to you when you sold the option in the first place. So, being short gamma means you don’t want a market move.

At a more detailed level, some would refer to a trader as being long gamma more specifically if they are purchasing ATM strike options, as this is where the gamma is the highest.

Now, let’s tie it all back together. If the bulk of market participants are option BUYERS, we could say that the market is long gamma. The implication of this is that the asset could experience a period of price stability.

Remember, with the sensitive ATM strikes, a trader who wants to be delta neutral / manage risk that owns the GBP/USD call option would have to sell GBP if it appreciated in value and buy GBP if it fell in value. Now imagine that this effect was magnified by many market participants who are long gamma. This would act to buy any dips and sell any rallies, capping the movement of the pair.

Low Gamma Structures

Based on the above, the combination of a structure that has a leg buying an option and one selling an option would help to make a structure have low gamma exposure.

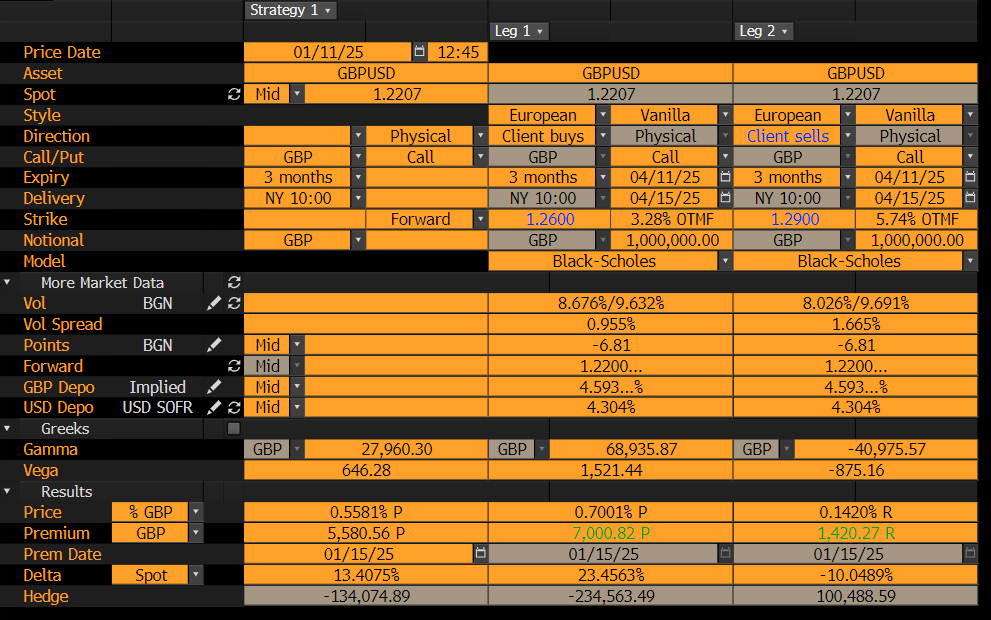

For example, let’s say that we turned our call option into a call spread, joining our bought 1.26 strike with a sold 1.29 strike. Note the gamma (first line under Greeks) as a result:

In contrast to a positive gamma of £69k, it now is reduced to £28k, thanks to the offsetting impact of selling the call which provides short gamma exposure to the structure.

Technically, if we sold the call at 1.2600, that would make our gamma zero.

With this call spread, it’s not completely gamma neutral as we want the underlying to trend higher to a point, but it does reduce the exposure by a significant degree.

Theta

Theta (Θ) measures the sensitivity of an option's price to the passage of time, also known as time decay. If your brain is slightly scrambled from delta and gamma, this is a rather easier one for us to end on.

It’s logical to assume that the value of an option decreases (all things assumed equal) as it gets closer to expiry. Our 3-month call option has less value than a 12-month one with the same parameters, and part of this is simply down to it having more time for the market to move over a longer period.

So, at a basic level, if you are long options (calls or puts), then you’ll have negative theta because their value diminishes as expiration approaches.

That’s why when we look at our theta exposure on our GBP/USD call, it’s negative:

However, you’ll also notice that it’s small. Each business day, we lose £78.50 in value from the option premium due to the theta decay.

Why Important

Time decay works against you as a buyer of an option. So, at a basic level, purchasing a vanilla option should really only be done if you anticipate a significant move in the underlying asset price BEFORE expiration. It sounds overly simple, but with the rise of retail interest in trading options, it can sometimes get confused with being the same as buying the underlying at spot. It’s not. The finite time of the option means that if you expect a move higher but don’t have a conviction for when it might happen, trade at spot instead of buying an option.

Another key point with theta is to kick out the expiry longer than you expect. Even if we expect a move to happen within a couple of weeks, it’s usually worth kicking out expiry to one month. That way, you’re a little more protected in case things take longer to materialise. Further, if the move does happen within two weeks, you can sell the option back with some time value still on it.

Finally, zero days to expire (0DTE) options should be understood as RISKY. The time decay is rapid, and although these can generate large profits, theta will eat away at the option premium rapidly.

Theta Trading

There are a couple of main ways to try and isolate theta. Firstly, becoming more theta neutral.

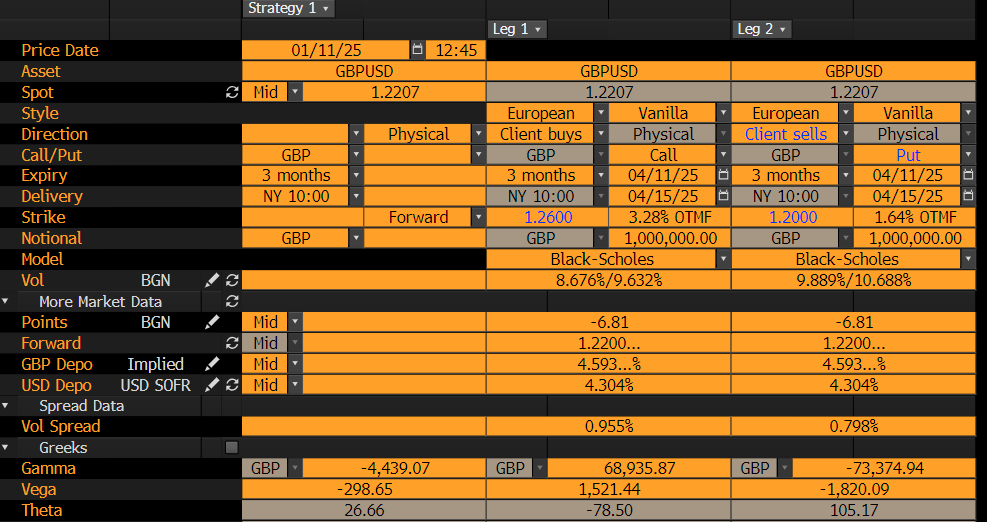

Imagine we kept our GBP/USD call, but we turned it into a risk reversal by selling a 1.20 strike put. As we are now selling an option (theta positive), the structure overall becomes theta positive (look at the bottom line):

This means that even though we’ll lose value on the call leg, the premium we net from selling the put will also decrease as time runs out, meaning we’re protected from the time decay.

The other scenario is simply to switch and build an entire strategy around selling options. In this case, theta is your friend, as it erodes the premium that you received. However, the old adage of picking up pennies in front of a steam train can be applicable here. As an option seller, you can open yourself up to potentially unlimited losses should the underlying have a sharp move in one direction. You can reduce this by structures like iron condors, but this removes the direct theta benefit and positions it more as theta neutral, which can defeat the whole point.

We hope you enjoyed this primer on some of the Option Greeks. Comments and opinions are welcome, as always.

Enjoy the weekend.

AlphaPicks

This was...EXCELLENT! Congrats.

You guy know I'm your Primer's most devoted reader.

Thank you for showing the Bloomberg screens and for using FX instead of options, it adds much more value as most people explain the Greeks mainly through equity.

If I many:

Although negligible, kindly consider that Delta isn't strictly the probability of the option ending ITM but rather Delta takes into account the amount an option can be ITM.

"By using Delta, the options analyst will slightly overestimate the ITM probability of call options. However, this discrepancy is negligible, especially in the presence of other sources of errors inherent in the Black-Scholes model used to compute these probabilities."

(https://medium.com/@rgaveiga/is-delta-the-same-as-in-the-money-probability-8df723bb4fe4)

"While a call can have an infinite payoff, a put’s maximum value is the strike (as spot cannot

go below zero). The delta hedge for the option has to take this into account, so a call delta must be greater than the probability of being ITM. Similarly, the absolute value (as put deltas are negative) of the put delta must be less than the probability of expiring ITM."

Negible, but a small mathematical difference that sometimes can lead to option miss pricing.

Quant Hedfe Funds are quick to identify these.

Hope to read more primers!

Cheers

S.

Cool