Global Primer Series: Precious Metals (Gold)

Understanding the unique dynamics of the gold market.

Gold moved from the periphery to the centre of the macro conversation in 2025. What began as a reallocation turned into a decisive repricing as investors searched for an asset that could absorb fiscal noise, policy uncertainty, and currency weakness without relying on growth, credit, or institutional promises.

Gold broke higher not as a speculative trade, but as a balance-sheet response to a shifting macro regime.

The precious metal sits at an unusual intersection of narrative and necessity. It is a currency without a central bank, a monetary asset without an issuer, and one of the few instruments that exists both inside and outside the financial system at the same time.

Unlike bonds, it carries no credit risk. Unlike currencies, it does not depend on policy credibility. Its value rises when confidence in monetary and fiscal frameworks begins to fray.

Investor demand in 2025 reflected deep concerns around real rates, fiscal sustainability, reserve diversification, and the long-term purchasing power of fiat money. As the dollar weakened and long-end bonds lost their defensive appeal, gold reasserted itself as a neutral reserve asset—one held not for yield, but for safehaven.

In this primer, we’ll consider the following:

Drivers of Price Action

Market Structure

Notable Historic Events

Unique Market Dynamics

Trading Strategies

Market Participants

Key Drivers

Gold price action is primarily driven by the opportunity cost of holding a non-yielding asset, which makes real interest rates (typically proxied by the 10-year TIPS yield) the core macro variable to watch: lower real yields reduce the carry disadvantage and support higher gold prices, while rising real yields exert downward pressure.

The US dollar is the secondary anchor. Given gold’s denomination and its role as a reserve alternative, dollar weakness generally corresponds with inflows into gold as global purchasing power improves and FX-hedged returns rise. Global liquidity conditions also play a significant role: periods of monetary expansion, QE, or abundant reserves tend to lower discount rates and increase portfolio hedging demand, while liquidity withdrawal or tightening cycles create headwinds.

Beyond macro rates and currency factors, central bank reserve-management flows have become increasingly influential, particularly among emerging market reserve managers diversifying away from USD exposure. This source of demand is strategic, price-insensitive, and structurally supportive.

Meanwhile, ETF flows, futures positioning, and CTA trend signals drive shorter-term moves, often amplifying directional momentum around data releases or macro inflexion points.

Finally, geopolitical risk and systemic stress function as convexity triggers rather than steady-state drivers: gold does not rise simply because uncertainty increases, but it tends to outperform sharply when confidence in policy, institutions, or cross-border capital mobility becomes impaired.

Market Structure

The global gold market is defined by a two-tier structure: a deep, liquid OTC market centred on the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA), and a highly standardised futures market anchored at COMEX in New York.

The London market is where the majority of physical and unallocated gold trading occurs, with bullion banks, central banks, refiners, and sovereign wealth funds transacting primarily through forwards, swaps, and spot transfers settled via London Good Delivery bars. This OTC system functions as the core pricing venue and liquidity pool.

COMEX, by contrast, provides financial leverage and price discovery through the GC futures contract, which is widely used by macro hedge funds, CTAs, and producers for hedging and speculative positioning.

Although futures volumes often exceed visible physical flows, most futures contracts are closed out or rolled rather than delivered, with the EFP (Exchange for Physical) mechanism linking COMEX futures pricing back into London spot liquidity.

Complementing these institutional venues are exchange-traded products such as GLD and IAU, which provide scalable retail and asset management access. Inflows and outflows in these vehicles influence custody holdings in LBMA vaults and therefore matter at the margin for spot.

Meanwhile, central banks now represent a structurally meaningful bilateral flow driver, accumulating physical reserves outside public markets and reinforcing the physical floor under the asset.

Notable Market Episodes

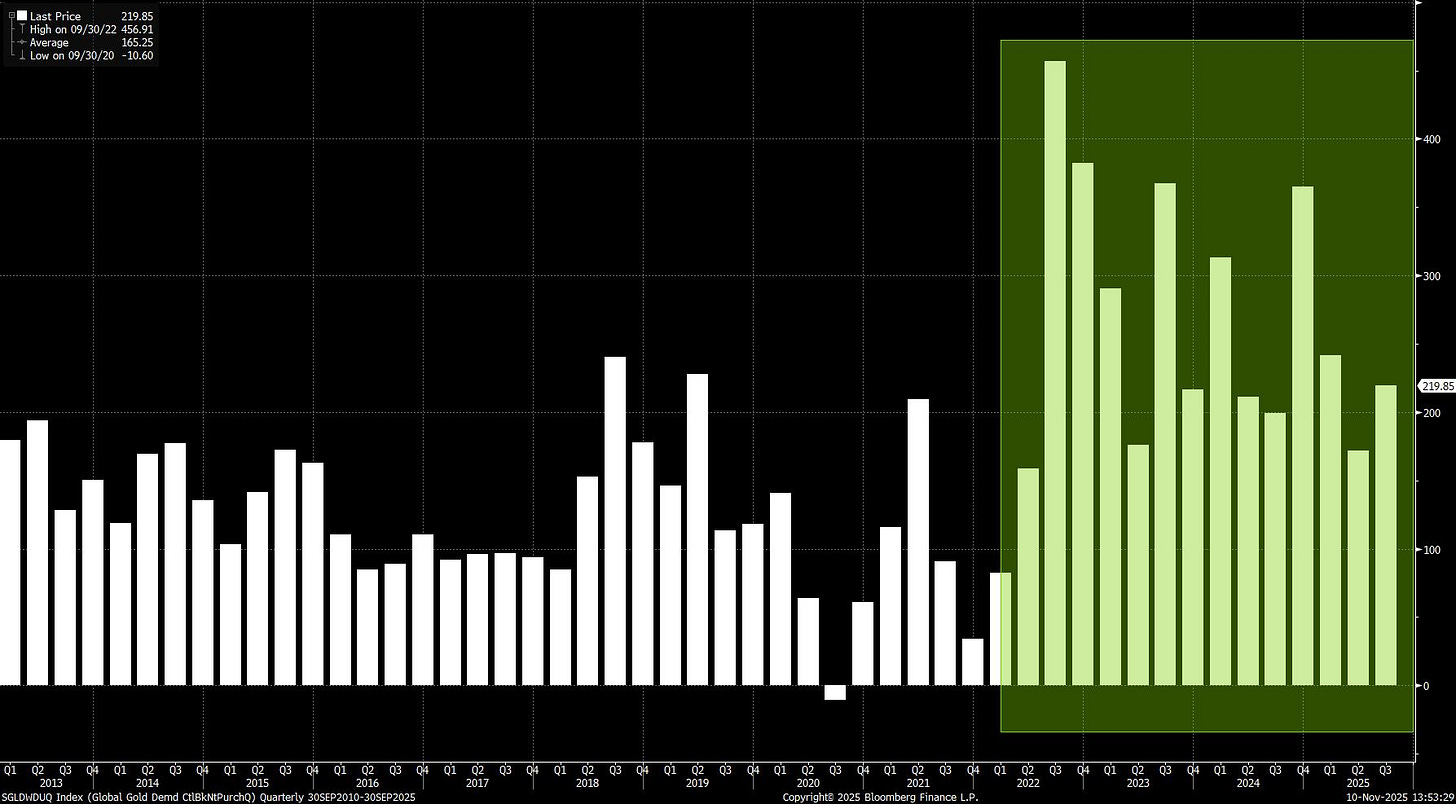

Gold’s modern trading history begins in earnest with the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, when the United States suspended dollar convertibility into gold. This decision transformed gold from a fixed-price reserve anchor into a free-floating monetary asset. From that point onward, gold began trading not as a static store of value, but as a dynamic barometer of monetary credibility, policy discipline, and global liquidity conditions.

The 1970s marked gold’s first major test in this new regime. A combination of expansionary fiscal policy, repeated oil shocks, and persistently negative real interest rates created an environment in which confidence in fiat money deteriorated steadily. Gold responded with a structural repricing, rising sharply throughout the decade and culminating in a dramatic peak in 1980. Over this period, gold prices increased by roughly 200%, reflecting not just inflation fears but a broader breakdown in monetary anchor points.

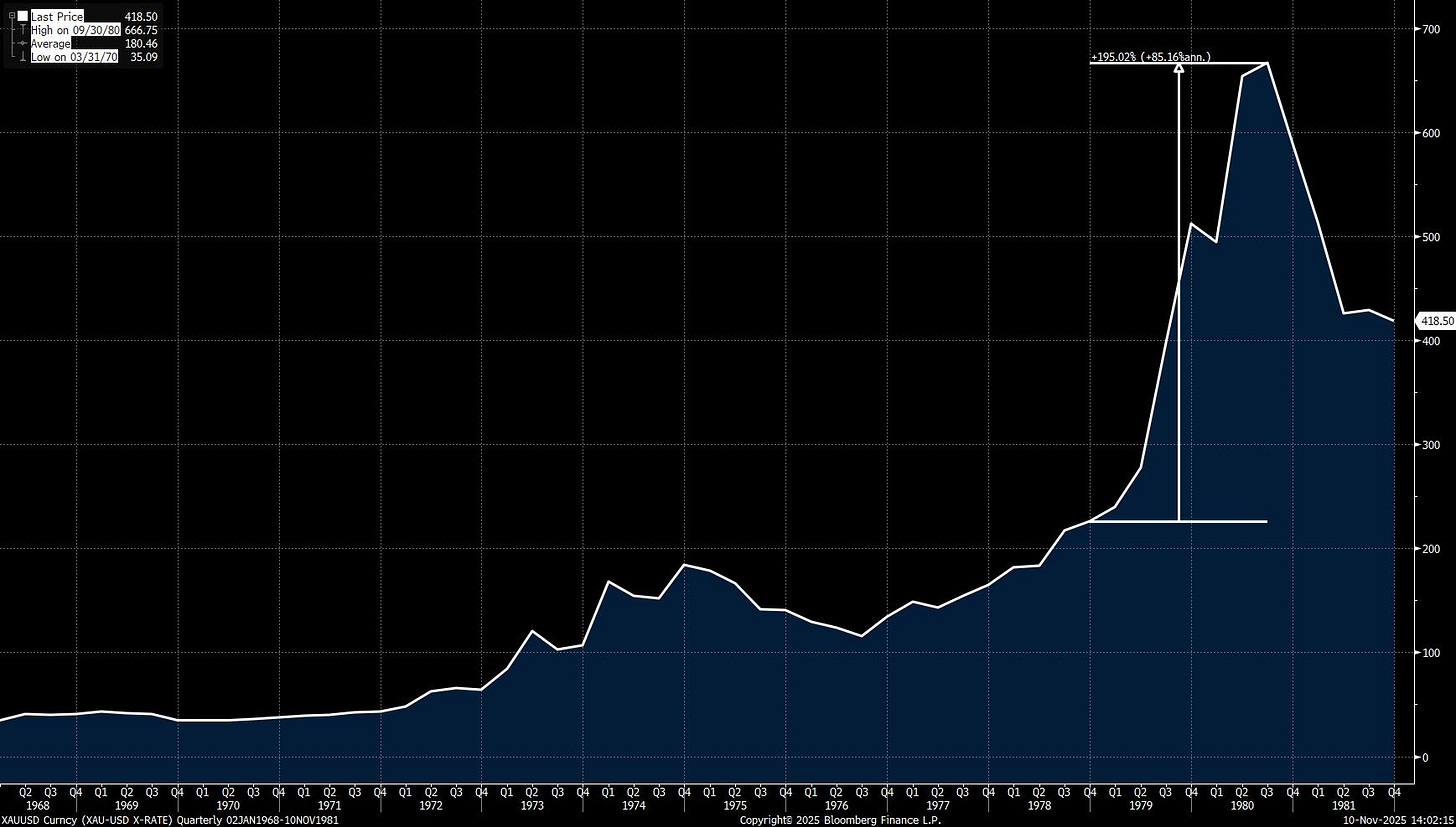

In contrast, the 1990s represented a prolonged period of disinterest and decline. With inflation subdued, real rates positive, and financial globalisation accelerating, gold came to be viewed by Western policymakers as a non-productive and increasingly obsolete reserve asset. Central banks in Europe and elsewhere became net sellers, contributing to a secular downtrend that saw gold prices fall to roughly $250 per ounce by 1999. That same year, the Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) was introduced to coordinate and cap official sector sales, helping to stabilise expectations around reserve flows and establish a durable price floor after years of erosion.

Gold’s role was once again redefined in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Between 2008 and 2011, collapsing real yields, systemic financial stress, and the introduction of large-scale quantitative easing programs restored gold’s relevance as a hedge against monetary regime uncertainty. The metal rallied strongly over this period, reflecting both fears of currency debasement and the repricing of long-term confidence in central bank balance sheets.

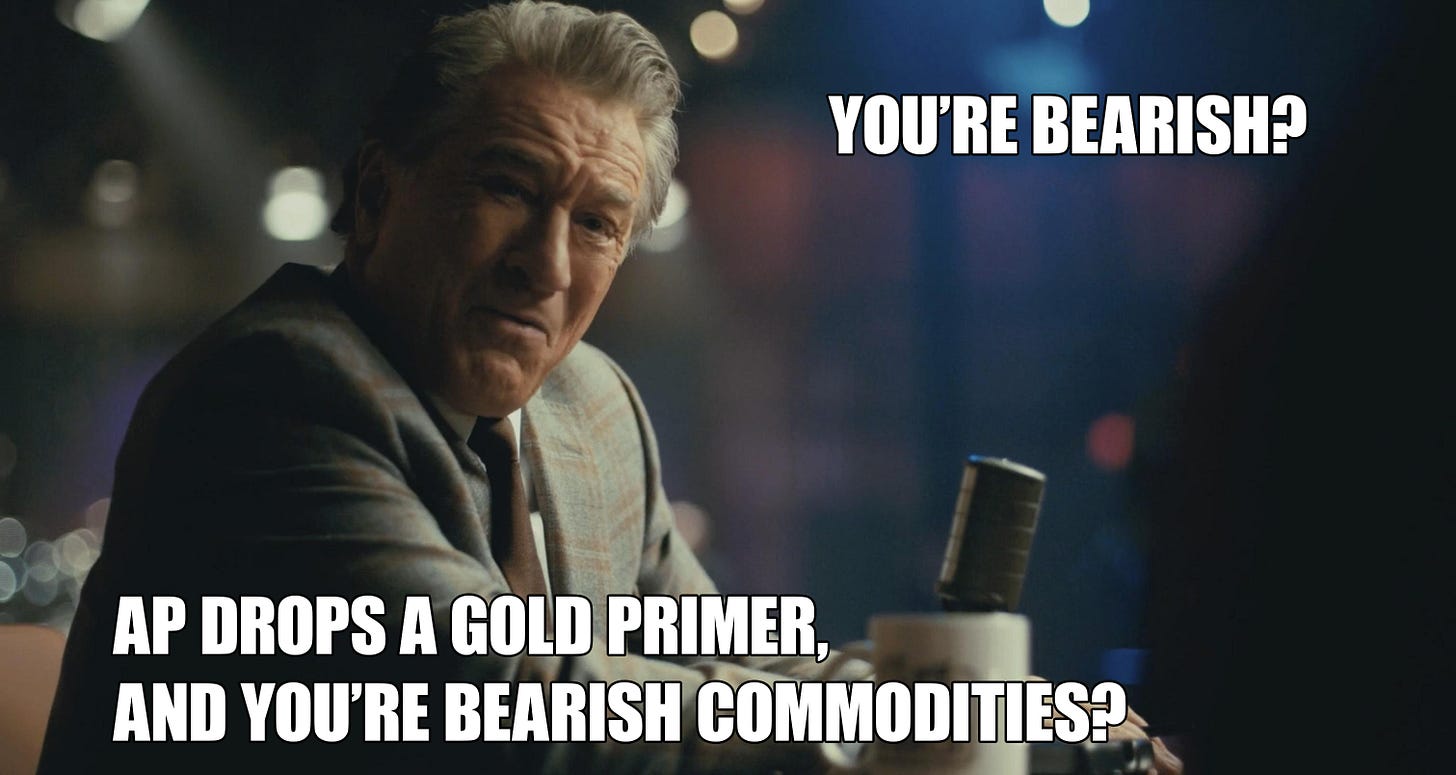

More recently, the post-2020 environment has reinforced gold’s appeal through a different channel. Pandemic-era fiscal expansion, rising public debt burdens, deglobalization pressures, and increased geopolitical fragmentation have all contributed to renewed central bank accumulation of gold reserves, particularly among emerging market economies. Unlike previous cycles, this demand has persisted even in periods where real yields remained positive, underscoring that gold’s support has increasingly been driven by concerns around policy credibility, reserve diversification, and the long-term stability of the monetary order rather than by inflation alone.

A Different Way to Think About Supply and Demand

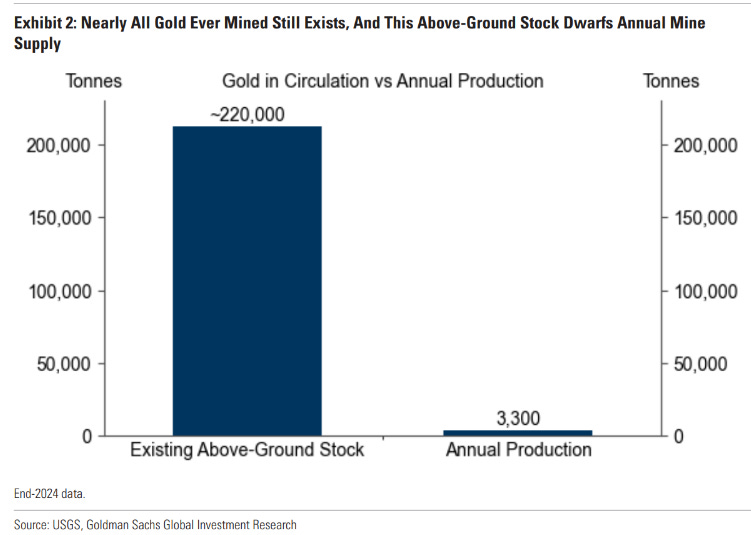

Gold does not behave like most commodities because it is not consumed. Nearly all the gold ever mined still exists, sitting in vaults, central bank reserves, or household balance sheets. The global above-ground stock is estimated at roughly 220,000 tonnes, while annual mine production adds just over 3,000–3,300 tonnes per year, a little more than 1% of total stock. This makes gold fundamentally a stock-driven market rather than a flow-driven one. Traditional supply–demand frameworks, which focus on balancing production and consumption, are therefore structurally ill-suited to explaining gold price dynamics.

Because annual mine supply is both small relative to existing stock and largely insensitive to price, gold does not clear through marginal production decisions. Miners cannot quickly increase output when prices rise, nor do they meaningfully curtail supply when prices fall. New projects take years or decades to develop, ore grades continue to decline, and most mines operate close to engineered capacity regardless of spot prices. As a result, changes in mine supply explain very little of gold’s short-term price behaviour. What matters instead is how much of the existing stock is available to trade.

Gold prices are therefore set by changes in ownership. When gold is bought, it must be sold by someone else, and the price adjusts until the identity of the marginal holder changes. In this sense, the gold market clears not through flows of new supply, but through the willingness of existing holders to part with their gold. The key question for price formation is not how much gold is produced, but who is more willing to hold it and what it takes to persuade someone else to let go.

This ownership dynamic creates a clear distinction between two broad types of buyers. Conviction buyers—central banks, physically backed ETFs, and macro or speculative investors—allocate to gold based on macroeconomic, financial, or geopolitical theses. Their demand is largely price-insensitive. When they want gold, they buy it regardless of level.

Opportunistic buyers, by contrast, are primarily households in emerging markets, where gold often functions as a form of savings. These buyers are price-sensitive, stepping in when prices fall and slowing purchases when prices rise. They rarely sell on net.

As a result, conviction buyers determine the direction of prices, while opportunistic buyers influence the amplitude of moves by providing a floor on the way down and resistance on the way up.

Empirically, this distinction matters. A report from Goldman Sachs on gold showed that net purchases by conviction buyers explain roughly 70% of monthly gold price variation. As a rule of thumb, every 100 tonnes of net conviction buying is associated with approximately a 1.7% increase in the gold price.

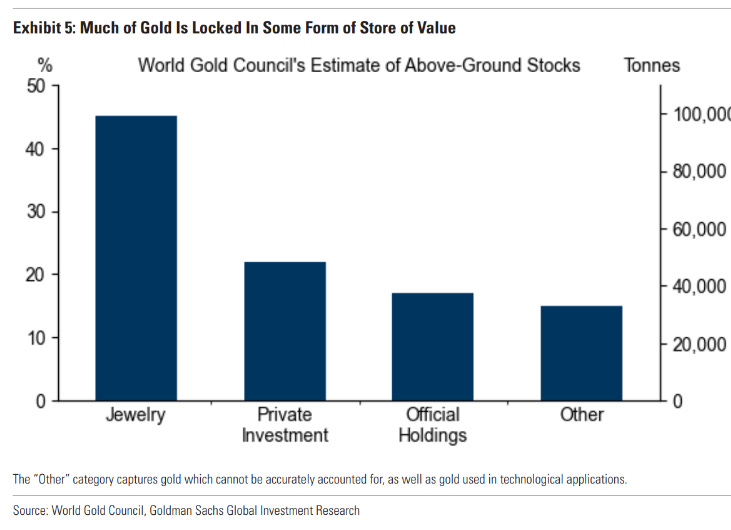

This relationship exists because the amount of gold that is actually available for sale at any point in time is small relative to the total stock, much of which is effectively locked away. Around 17% of above-ground gold sits in central bank reserves, roughly 22% is held in investment vaults, and a large share of the remainder is held as jewellery in emerging markets, where it is rarely mobilised for sale.

This structure explains why the traditional commodity adage that “high prices cure high prices” does not apply to gold. Rising prices do not unlock large volumes of new supply, nor do they induce widespread selling from opportunistic holders. When conviction buyers are net buyers, prices can rise sharply and persistently because there is no meaningful supply response to arrest the move. Gold prices only fall decisively when conviction itself breaks, and those same buyers step back.

At the most basic level, the market clears when conviction and opportunistic buying together absorb mine supply and any sales from existing holders. In practice, because mine supply is stable and opportunistic buyers rarely sell, most adjustments occur through conviction holders trading among themselves. This is why gold can remain supported despite positive real yields, fall during periods of elevated inflation, or rise even when ETF flows are negative, provided central banks or other conviction buyers are accumulating.

The practical implication is that gold is not a market where balance tables or production forecasts provide much insight. Understanding price action requires tracking who the marginal buyer is, whether conviction demand is expanding or contracting, and how much gold is actually available to be prised loose. In gold, price is not set by how much is produced, but by how much conviction it takes to change hands.

Trading Strategies

Gold offers a wide menu of trade expressions that extend well beyond outright spot or futures exposure. Most strategies are ultimately about isolating which transmission channel an investor wants to target.

Real Rates Expression

The most fundamental gold trade is a view on real interest rates. Gold has a persistent negative correlation with US real yields, particularly at the long end, making it an efficient way to express expectations around easing financial conditions, policy pivots, or declining term premia.

This can be implemented through:

Long gold futures or XAU/USD against short real rates exposure (e.g. TIPS)

Relative trades versus long-end Treasuries when bonds lose their defensive properties

Gold often outperforms bonds when real yields fall for the “wrong” reasons. We’re talking about fiscal dominance, volatility in inflation expectations, or credibility concerns, rather than clean disinflation.

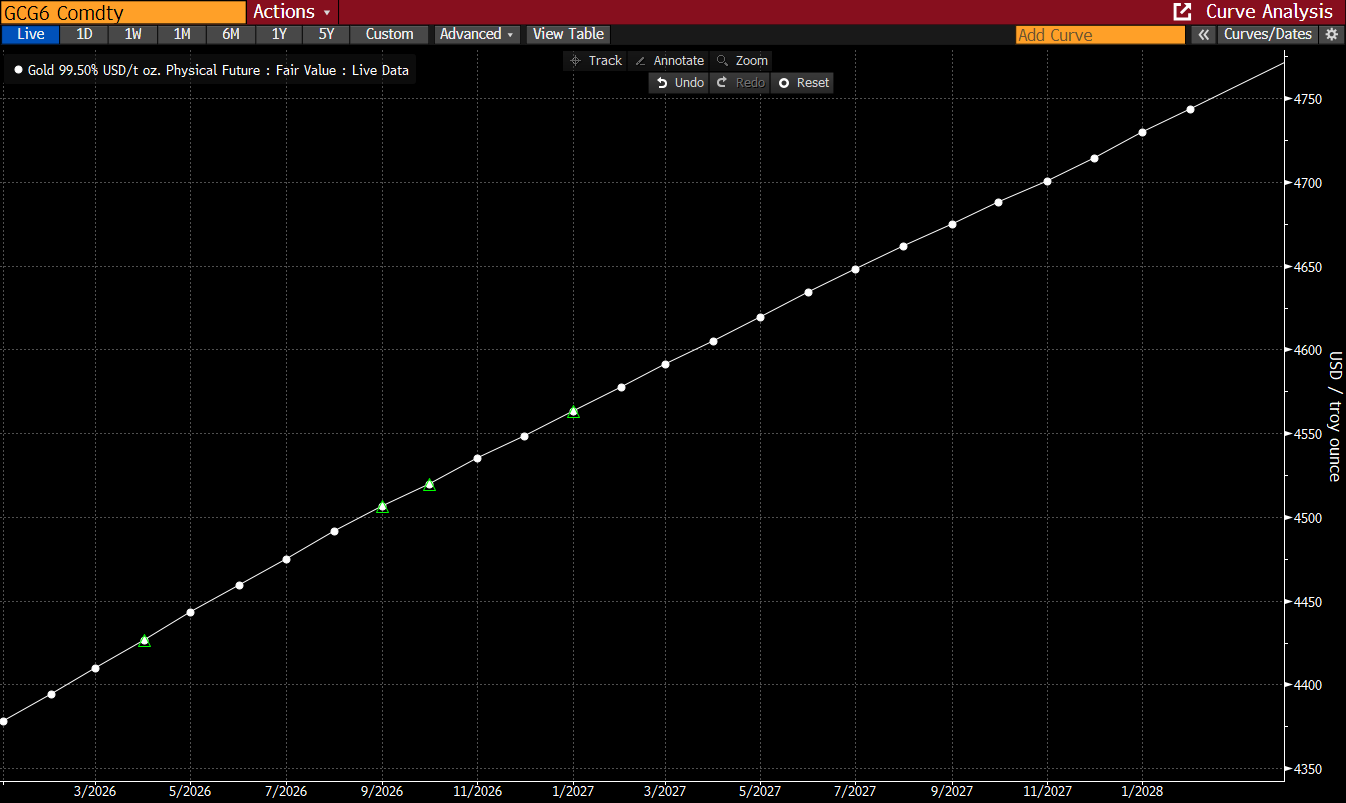

Curve and Carry Trades

While gold is typically in contango due to storage and financing costs, distortions can emerge when lease rates, USD funding conditions, or physical tightness move out of alignment.

The current (and typical) curve looks like this:

In contango environments, investors can implement carry trades by holding physical or allocated gold while shorting futures further out on the curve. In rarer backwardation episodes (usually driven by temporary physical dislocations) spot can trade higher than futures, creating inventory-replacement opportunities.

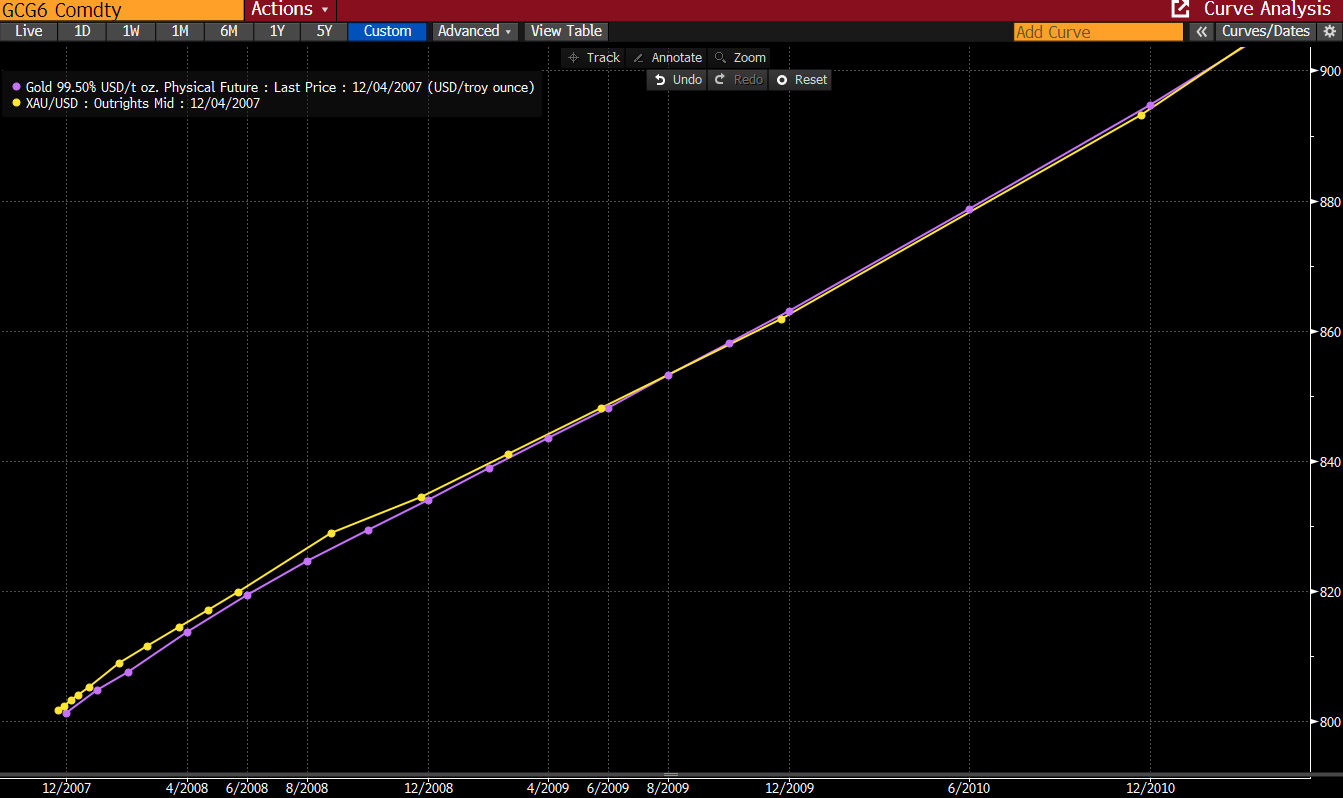

Typically, gold futures trade in parallel with gold forward contracts (XAU/USD), but there are periods when dislocations occur, creating arbitrage opportunities. For example, during 2008/2009, when the financial crisis was causing chaos around the world, there were differences in pricing, illustrated below.

Returns in these trades are driven by financing spreads and curve shape, not by outright price direction, making them attractive for relative-value or balance-sheet-constrained investors.

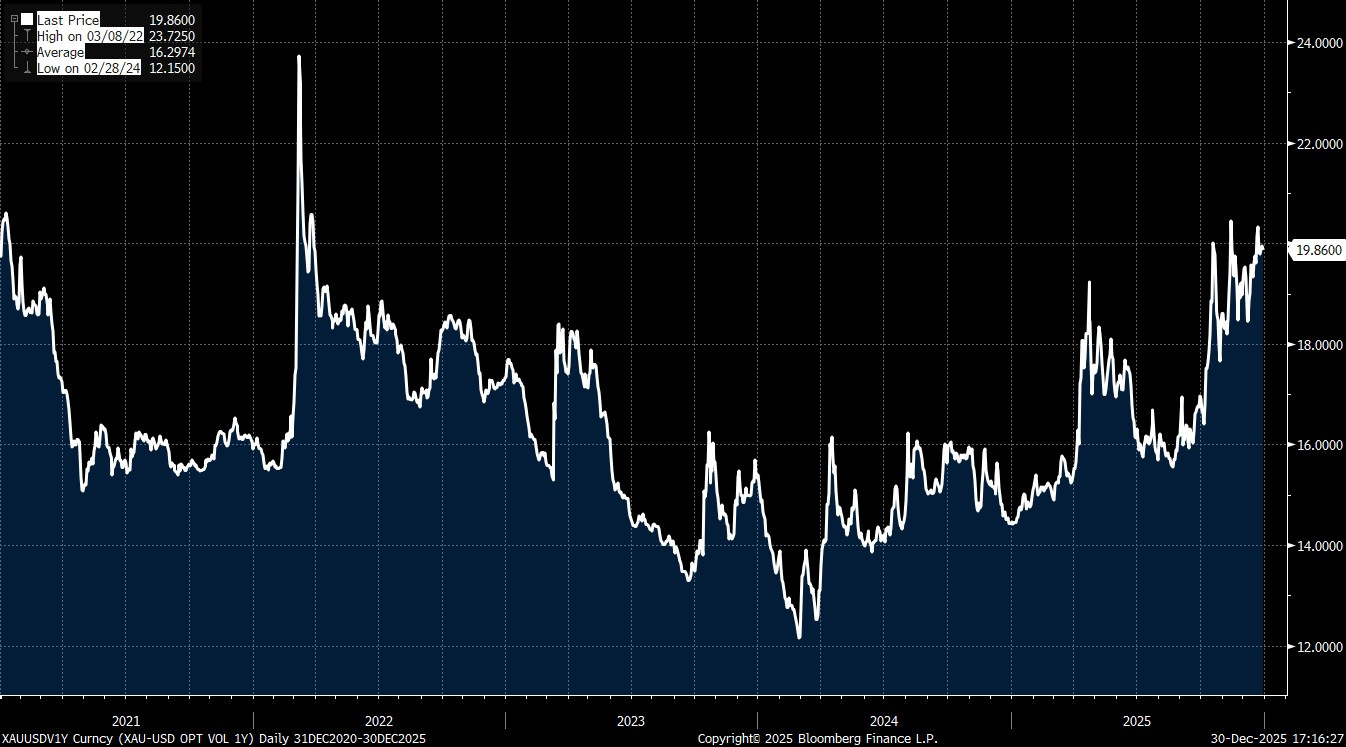

Volatility and Options Structures

Gold options provide a clean way to express convex views on macro stress, regime shifts, or tail risks. Demand for downside protection and upside convexity often shifts asymmetrically depending on whether gold is being used as a hedge or a speculative instrument.

Common strategies include:

Long volatility during periods of compressed implieds despite elevated macro uncertainty. Reviewing the historical ATM volatility is the easy part. Deciding if it’s cheap enough to buy is harder…

Skew trades occur when call demand from hedgers or reserve managers distorts pricing

Long-dated optionality captures regime risk rather than short-term data outcomes

Gold volatility tends to reprice sharply around policy inflexion points, debt sustainability debates, or currency regime stress.

ETF Flow and Physical Dislocation Trades

Physically backed ETFs introduce an additional transmission mechanism into gold pricing. Large creation or redemption cycles can temporarily push ETF prices away from underlying spot or futures markets due to settlement and inventory mechanics.

When dislocations arise, relative trades can be constructed by:

Buying spot or futures and shorting ETFs during redemption pressure

Buying ETFs and shorting futures when creation demand outpaces physical sourcing

These opportunities are episodic and capacity-constrained but can be attractive for well-capitalised arb desks.

Gold Equities as a Levered Expression

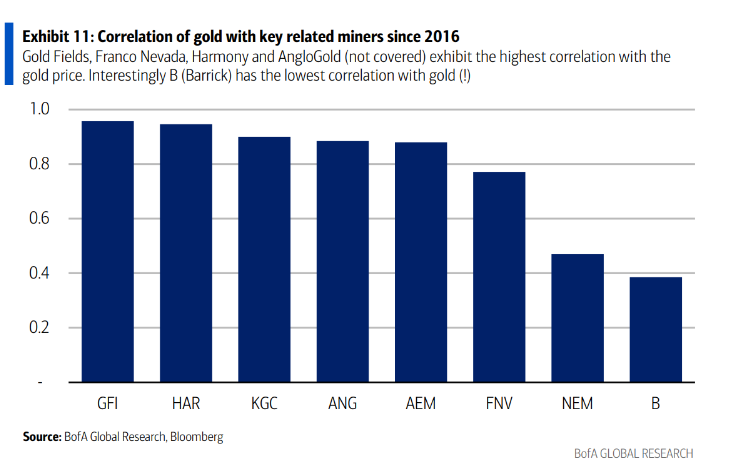

Gold equities provide an alternative way to express gold views, but with important caveats. Unlike gold itself, equities embed operational risk, cost inflation, jurisdictional exposure, and capital allocation decisions.

That said, correlation analysis shows meaningful dispersion in how closely different gold equities track the underlying gold price. Companies such as Gold Fields, Agnico Eagle, and Harmony Gold exhibit relatively high sensitivity to gold price movements, making them more suitable for directional gold exposure.

By contrast, firms like Barrick Mining show lower correlation due to diversification into copper and other assets, reducing their purity as gold proxies. Streaming and royalty companies such as Franco-Nevada offer gold exposure with lower operational risk but often trade more like long-duration financial assets, making them sensitive to discount rates as well as gold prices

Single-name positioning can therefore be used to express higher beta to gold through operationally geared miners, as well as having trade dispersion between “pure play” gold exposure and diversified balance sheets.

Market Participants

The gold market is shaped by a relatively small but highly specialised group of participants whose motivations span reserve management, balance-sheet intermediation, portfolio hedging, and speculative positioning. Unlike industrial commodities, end-use demand plays a limited role in price discovery. Instead, gold prices are set at the margin by institutions with the balance sheet capacity to accumulate, warehouse, or mobilise large stocks of metal.

Central Banks and Sovereign Institutions

Central banks are the largest and most price-insensitive buyers of gold, accumulating reserves for diversification, credibility management, and geopolitical risk mitigation.

Their activity (largely conducted via the LBMA) provides a structural floor for gold demand. Sovereign wealth funds and state investment agencies play a similar role, often allocating through physical holdings or OTC swaps. These participants have multi-year horizons and minimal sensitivity to short-term volatility.

Bullion Banks and Dealers

Global bullion banks (like JPM and HSBC) are the core liquidity providers. They intermediate between miners, refiners, ETFs, industrial users, and macro funds. Their books span physical inventory, unallocated accounts, forwards, swaps, and exchange-traded futures.

They manage complex carry books tied to USD funding conditions, lease rates, and client hedging flows. Bullion banks also maintain the arbitrage link between LBMA spot and COMEX futures, anchoring global price coherence.

Miners and Producers

Gold producers participate in the market primarily as risk managers rather than price setters. They hedge future production using forwards, swaps, and futures to stabilise cash flows and lock in margins. This hedging activity can generate persistent selling pressure in longer-dated maturities, particularly during sustained price rallies, but it has limited influence on spot prices.

Because gold mining supply is price-inelastic and planned years in advance, producer behaviour rarely drives short-term price dynamics. Instead, miners function as predictable, slow-moving counterparties whose activity matters more for curve shape than for outright price direction.

ETFs, ETCs, and Physically Backed Vehicles

Large physically backed ETFs create meaningful, price-sensitive investment flows. They serve as the primary access point for asset managers who cannot hold bullion directly. Inflows and outflows mechanically adjust physical demand through creation/redemption processes, making ETF flows a crucial indicator of investment sentiment. Europe’s ETC market plays a comparable role for institutional allocators outside the US.

Hedge Funds, CTAs, and Macro Traders

Speculative capital (largely via COMEX) drives short-term price discovery. Macro funds express views on real rates, USD liquidity, and risk appetite via gold futures or XAU/USD.

CTAs and trend-following systems amplify momentum, particularly in gold and silver. Relative-value specialists trade cross-metal spreads such as gold/silver or platinum/palladium to capture substitution cycles and curve dislocations. These players bring liquidity but also increase the market’s reflexivity.

Retail Investors and Physical Buyers

Retail participation in the gold market is geographically concentrated and highly cyclical. In emerging markets (particularly India and China) physical gold ownership serves as a form of household savings rather than discretionary consumption. This demand is price-sensitive, rising sharply during pullbacks and slowing during rallies, and it rarely turns into sustained net selling.

In developed markets, retail investors primarily access gold through coins, bars, and ETFs, with participation spiking during periods of macro stress or heightened volatility. While retail flows can overwhelm short-term liquidity during extreme episodes, they generally act as stabilisers rather than directional drivers.

Conclusion

Structurally, gold is a market defined by ownership rather than production. Supply is slow, predictable, and largely irrelevant at the margin. Price is set by conviction: by central banks, institutional investors, and macro allocators willing to warehouse trust when other assets demand it. Opportunistic demand smooths the path, but it is conviction that determines direction.

Gold is not a market to be analysed through balance tables or short-term narratives. It is a market where understanding the marginal buyer matters more than forecasting mine output, and where positioning, liquidity, and credibility interact in non-linear ways. Whether expressed through spot, futures, options, ETFs, or equities, gold remains one of the cleanest ways to engage with regime risk.

In an environment defined by rising debt, political constraints on policy, and an increasingly fragmented global system, gold’s role is unlikely to diminish. It may not always outperform. It may spend long periods consolidating. But when trust becomes scarce, gold has a habit of reminding markets why it still matters.

If you enjoyed this Primer, please drop a like or comment below. If you want to read more Primers, check out the library here.

AP

Excellent primer on Gold here

Is there a way to track central bank flows for gold? Also really interesting part around the price insensitiveness and the case where it’s proportional to real yields going up