Outperformance Is Scarce

Over the last five, 10 and 15 years, how many actively managed funds have beaten the Nasdaq 100? Just one.

Skewness creates big outliers in a huge distribution of outcomes. Stock pickers never had a chance against the math. Over the last five, 10 and 15 years, how many actively managed funds have beaten the Nasdaq 100? Just one.

At first, it seems hard to believe. But the math is stark. The fund’s success can be attributed to picking two dozen companies and riding almost all of them to significant gains.

Who is the one and only fund? Baron Capital. Ron Baron, an 80-year-old Wall Street veteran who oversees the fund, says his secret is in his profound confidence in certain entrepreneurs, such as Elon Musk, and his paranoia to stay on top of everything that each company is doing, even to the point of calling them to make sure nothing is amiss.

However, this success is hard to copy. But it does create an interesting paradox to consider. Trying to beat the market by betting big on a handful of names is a strategy with exceedingly dismal odds. However, because of the tech-powered rally of the Magnificent Seven, it is the only way to do so.

The reason why this strategy would lead to so many portfolios crashing and burning is because the market produces such a scarce amount of winning stocks. That is why this strategy has only seen one winner in the last 15 years.

The active-management debate

The futility of playing against benchmarks like the Nasdaq 100 was underlined in a report last month by Bloomberg. This report had a response from Chamath Palihapitiya, who said indexes provided superior gains “without you having to do any work or diligence.”

Intellect and hard work are pretty useless, it turns out, thanks to dynamics that have increasingly come to dominate the active-management debate.

“Concentrated stock positions are significantly more likely to underperform than to outperform the stock market as a whole over the long term,” wrote Petajisto, currently head of equities at Brooklyn Investment Group. “Trying to gamble on identifying those few stocks with outsized returns would be a bad idea.”

The number of equities that have met that benchmark return can be pitifully small, even in a US market that has increased sixfold since the global financial crisis. The typical 10-year return among the 3,000 largest US equities has, in fact, trailed the general market by 7.9 percentage points over the previous century.

In the winner-take-all nature of the modern economy, the trend may perhaps be accelerating. While the Russell 3000 is up 15% in 2023, the median return is about a 0.7% drop. Approximately half of the constituents are down.

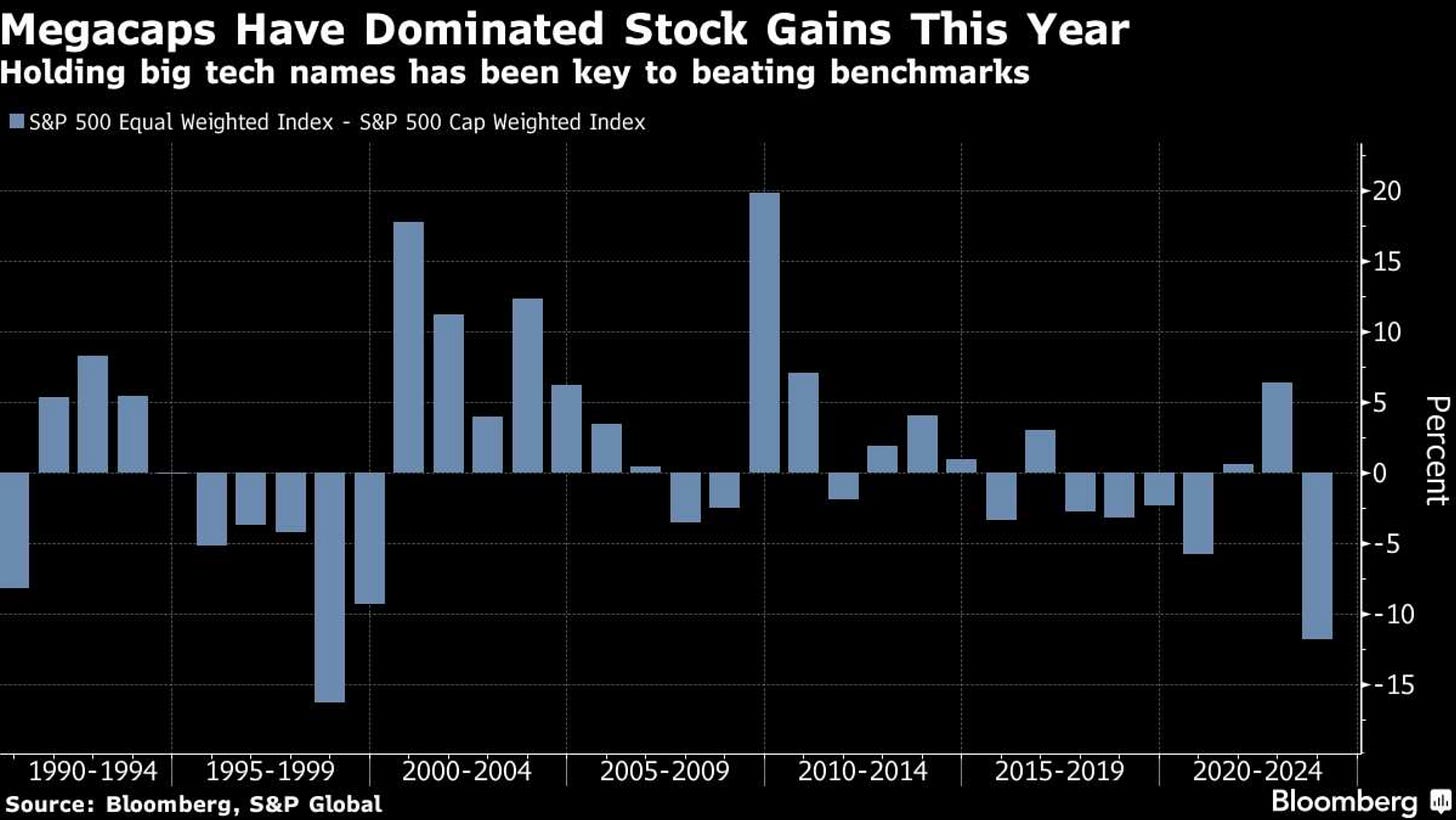

Another way to illustrate this is through the S&P 500 equal-weight index. It has trailed the value-weighted index by 12 percentage points this year, currently on track for the worst underperformance since 1998.

So what do active managers do? Do they follow the index and receive criticism of the high fees for doing nothing? Or do they deviate from the index and risk missing out on the big gains of the winners (which is where probability puts them because there are so few), and they, in turn, underperform the benchmark?

As you can guess, a large portion of managers who held all Magnificent Seven stocks beat their benchmarks over the past 12 months. But holding all seven names was a rare occurrence. Just 18% of 971 mutual funds owned all seven names, while 21% held none of them.

"Beating benchmarks, underpinned by those same seven stocks, required managers to make other fortuitous picks," David Cohne, a Bloomberg Intelligence analyst, said in a note.