UK politics has moved from a brief post-election honeymoon into something closer to managed instability. Prime Minister Starmer’s approval ratings have deteriorated sharply as voters struggle to connect Labour’s technocratic tone with any tangible improvement in daily life.

That weakness has opened the door to the first murmurs of internal dissent. So far, we haven’t seen outright coups, but there’s enough background noise for leadership threats to feel plausible if the party’s polling slide continues.

Chancellor Reeves, once positioned as the steady hand of economic credibility, is now carrying the heaviest burden. The upcoming budget has become a political and fiscal headache. If Reeves pitches too much towards austerity and breaks any of the three main tax pillars included in the manifestos, Labour risks accusations of betrayal. If she’s too loose and she spooks the gilt markets, the Truss/Kwarteng fiscaco might look like a minor inconvenience.

Put simply, everyone from institutional rate desks right through to grandma in the north of England is already wary of the UK’s debt dynamics.

Welcome to Rachel’s Reckoning.

The Delicate Dilemma

Labour came into power promising a tightly defined set of tax commitments: no rises in income tax rates, national insurance for employees, or VAT, and a cap on corporation tax at 25% for the full Parliament.

Those pledges were designed to signal stability and reassure voters after a decade of erratic fiscal policy. But the reality facing Reeves is far harsher than the manifesto’s assumptions allowed. The UK’s public finances now show a fiscal shortfall variously estimated at £30–50 billion, with some five-year projections stretching closer to £100 billion once downgraded productivity forecasts and higher debt-service costs are included.

Even the most conservative numbers (around £22 billion just to keep public services standing still) imply a structural gap that the government cannot ignore.

This leaves Reeves in an awkward position for the budget next week, in that she needs to raise revenue without breaching the headline tax promises that helped Labour win power.

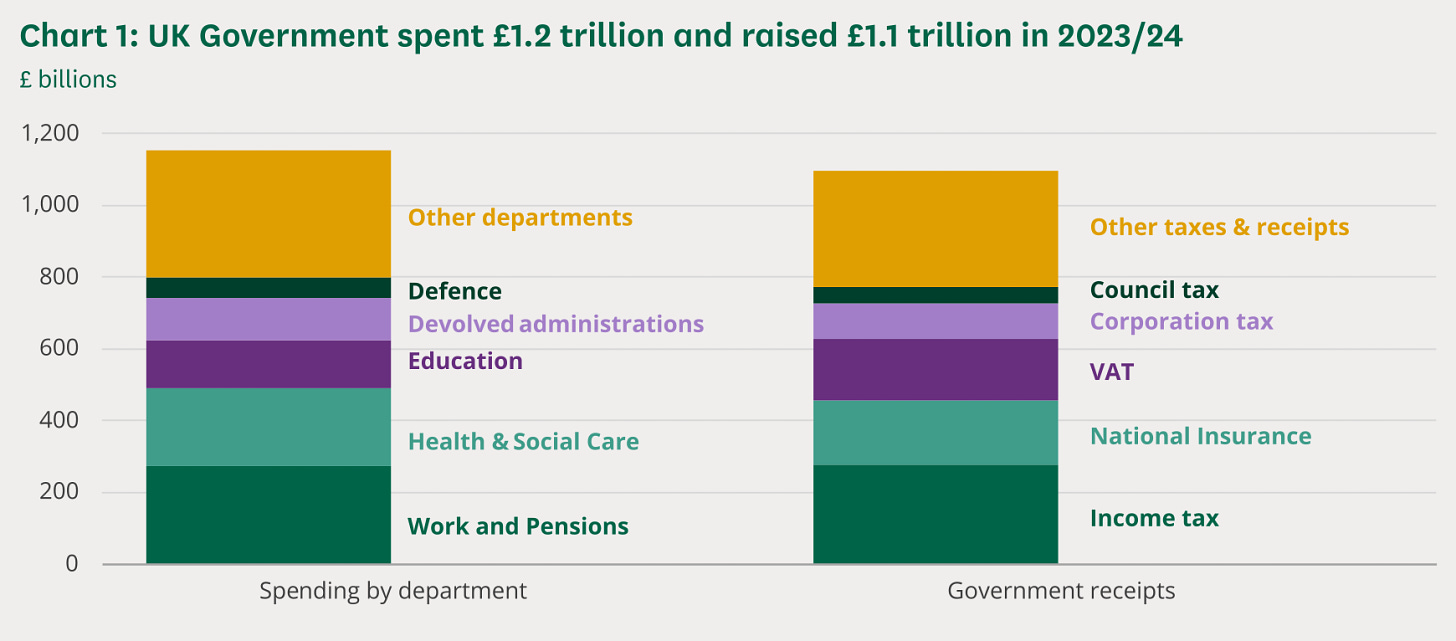

The current composition of Government receipts highlights the difficulty of boosting revenue when key sources (such as income tax) are off-limits.

As a result, attention has turned to measures that sit around the manifesto rather than through it. Freezing income tax thresholds, which quietly pulls more earners into higher tax bands, is a near-certainty and could raise £7–10 billion.

Reforming reliefs are also very much on the table. These range from pensions to dividends to specific business allowances. Each measure offers more scope for revenue without touching the protected headline rates. Wealth-focused measures, including changes to non-dom rules or second-home taxation, remain politically attractive. And while corporation tax may be capped, pressure is building around employer contributions and the broader business-tax ecosystem.

The fiscal hole is too large for cosmetic tweaks, but breaking manifesto pledges outright risks the government’s political credibility at a delicate moment.

In this note, we run through the budget’s implications for specific asset classes, drawing on insights from good friends (and experts in their respective fields), then present our own actionable ideas across markets.

Politics & Macro

From Ryan Paisey, Founder at PiQ

The political dimension of this budget cannot be separated from its economic consequences.

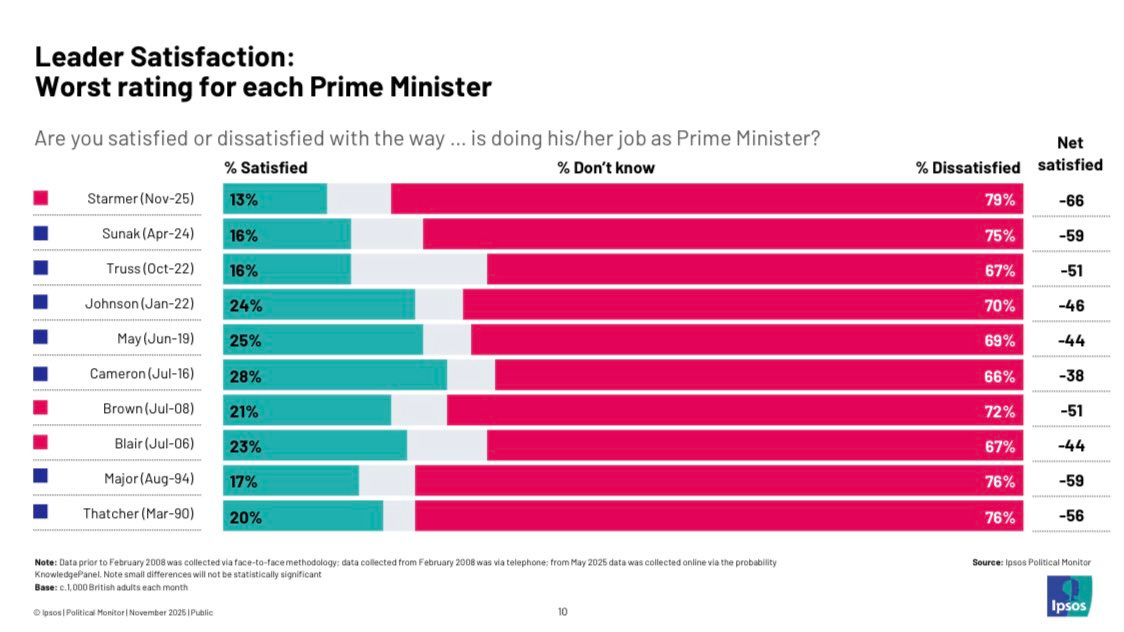

Starmer’s net satisfaction score stands at -66, placing him ahead of Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss, and even beyond alongside Gordon Brown, Boris Johnson, and Margaret Thatcher as among the weakest Prime Ministers at similar points in their first terms, while polling shows 56% of voters think the Prime Minister should step down, with 57% believing the same of Rachel Reeves.

Yet the uncomfortable truth for markets is that, as damaged as Reeves’ credibility may be, the alternatives are considerably worse. The obvious Treasury replacement would be Torsten Bell, whose enthusiasm for aggressive taxation would likely trigger the gilt market panic everyone is working to avoid.

Splinter groups within the Labour Party are beginning to prepare for a leadership contest, but the names being floated from various factions across the party represent politicians who are woefully inadequate for navigating a fiscal crisis.

The political calendar compounds this dynamic, as Labour faces local elections on 7 May 2026. Significant losses are widely expected. Any serious challenger would be better served waiting until after May’s drubbing to pin the blame on Starmer and Reeves.

What this means in practice is political purgatory. Markets know this government is finished, but the exit sits beyond May 2026.

We have a lame-duck Government trying to maintain fiscal discipline while lacking the authority to enforce it.

This is why a number of analysts are identifying politics rather than fiscal policy itself as the biggest risk to gilt markets. Any leadership challenge could raise concerns about fiscal discipline, particularly if it led to a more left-leaning chancellor replacing Rachel Reeves. The “better the devil you know” principle applies with unusual force. Reeves may lack credibility, but she understands that breaching fiscal rules triggers market crises. Her likely replacements either don’t grasp this reality or don’t care.

The base case isn’t a functioning government delivering sensible policy. It’s a mortally wounded administration stumbling toward May 2026 while trying not to spook markets.

Put another way, in my view, the real tail risk isn’t Reeves failing. It’s what comes after her.

A leadership contest producing a more left-leaning Treasury team could transform today’s manageable fiscal concerns into a confidence crisis.

FX & Rates

From Michael Brown, Senior Research Analyst at Pepperstone

Perhaps the simplest way to look at UK assets in the run-up to the Budget is to look at Gilts as a barometer of fiscal risk, and at the GBP as a pressure release valve for if, or indeed when, that fiscal risk grows too great.

Naturally, looking at Gilts in isolation doesn’t tell us especially much, given that the direction of travel is almost always identical to that of other DM govvies. Instead, a much better gauge of the market’s perception of UK fiscal risk is to look at the spread on the 10-year Gilt yield, over that of the next highest G7 benchmark – a market that’s been nicknamed a ‘moron premium’ by those less charitable than I!

Perhaps surprisingly, this spread was actually slowly but surely fading away for much of the pre-Budget period, from over 60bp in mid-September, to as tight as 25bp in mid-November, in a sign that while market participants had accepted that the upcoming fiscal consolidation would largely take the form of sizeable tax hikes (most notably an increase in income tax which, while far from being the ‘best’ option given the obvious negative impact on personal consumption, was the ‘least bad’ of the options available), with the government both unwilling, and seemingly unable, to enact sizeable spending cuts.

Energy

By Doomberg

Last week, Doomberg put out an article titled Late Britain. In it, the team laments a compounding failure of energy policy, industrial strategy and political will. When it comes to the key energy sector, there are some good takeaways ahead of the budget.

To begin with, Reeves will have to decide on the Energy Profits Levy (EPL). As Doomberg notes:

“Although the Californication of the British energy regulatory regime has been decades in the making, it reached its zenith in May of 2022, when Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak introduced a windfall profits tax on oil and gas companies. Ostensibly, the move was in response to soaring energy prices and was originally set to expire in 2025. Instead, the Energy Profits Levy (EPL) has been raised twice and extended to 2030, leaving energy companies facing a stifling 78% marginal tax rate. It’s no wonder the stampede for the exits has been disorderly.”

A few weeks ago, the Financial Times published a classic trial balloon about her thinking:

“Chancellor Rachel Reeves could scrap a windfall profits levy on the UK oil and gas industry sooner than expected, after Prime Minister Keir Starmer said he wanted to ‘double down’ on North Sea extraction.

Reeves is considering using her Budget to end the energy profits levy in March 2029—reversing a decision in last October’s Budget to extend it by a year to March 2030—according to people briefed on her thinking.

But the chancellor, under fierce fiscal pressure in her Budget, is seeking assurances from oil and gas companies that the move would result in new investment and jobs, and ultimately more tax revenues for the exchequer.”

At the start of November, Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) and Scottish Renewables sent a letter to the Chancellor calling for the EPL to be replaced urgently, the first time both groups have made such a joint effort. It warned that “we face a widening gap in jobs, investment and capability that will weaken our economy.”

This follows on from an OEUK letter signed by more than 110 companies. It noted:

“We are witnessing an accelerated decline in activity that is undermining the value of the sector and the supply chain capability we need for our energy future. Job losses are occurring at an unacceptable scale, and there is an urgent need for supportive policy to unlock investment, drive economic growth, and safeguard the UK’s energy transition.”

Doomberg concludes his piece by noting the following.

“This is the political backdrop against which Reeves will soon decide the fate of the EPL and, with it, what’s left of British heavy industry. If she flubs the Autumn Budget, Britain could be thrown into a bond-market crisis like the one that crippled Truss. If major changes to the EPL are not proposed and ultimately passed in Parliament, the country’s economic death spiral will likely accelerate. If she does try to scrap the tax, she’s likely to face fierce opposition from the Miliband wing of the Labour Party.

One way or another, Reeves will soon confront a historic fork in the road. Let’s hope she takes it.”

AP Trade Ideas

The UK heads into Budget week with political capital draining, market patience thinning, and a structural fiscal problem that can no longer be smoothed over with clever wording or marginal tweaks.

Even though pessimism has partly been priced in, there’s still a long way to go for some assets, depending on what exactly gets announced next week. Time to distil the above thoughts into tangible ideas.

Macro Angles

Rates: Long UK 2s30s