The Race for Rare Earths

As oil once was, minerals are now a tool of leverage.

China doesn’t need to fire a shot to remind Washington who controls the battlefield. In 2025, the front lines are tariffs and export licenses. It can simply tighten the valve on a handful of elements the general public has never heard of. Neodymium, dysprosium, terbium, obscure names with outsized power. They sit quietly inside iPhones, wind turbines, and F-35 jets, the invisible circuitry of modern strength.

Leader Deng Xiaoping said back in 1992 that “the Middle East has oil, China has rare earths.”

For years, this advantage was theoretical. Then Beijing started playing the rare-earth card. Export licenses are diplomatic weapons. Magnets are leverage. And suddenly, the world’s most advanced economy realised it was short on the materials that make everything else work.

Now the US is fighting back. Fiscal muscle is being rerouted into mines, refineries, and magnet plants from California to Western Australia.

This note traces that contest through four lenses:

Beijing’s control over supply

Washington’s pivot to local miners and Australia

The long-dated call option in Brazil

How we’re positioned and our thematic basket

First Off, Rare Earths 101

What are they?

Rare earths refer to a group of 17 metallic elements with exceptional optical, magnetic, and electrical properties. They sit at the heart of modern technology: terbium and yttrium bring colour to smartphone and TV screens; cerium scrubs pollutants in catalytic converters; neodymium and praseodymium power the permanent magnets that drive electric vehicles and wind turbines.

How rare are rare earths?

Despite the name, these elements are not geologically scarce. Cerium is more abundant than tin or lead. The challenge is concentration. Economically viable deposits are limited, and refining them requires energy-intensive, chemically complex processes. Most ores also contain radioactive byproducts like thorium and uranium, making environmental management a significant cost factor.

Who controls supply?

The United States once dominated production through the 1970s, but China’s low-cost expansion reversed that hierarchy. Today, China accounts for roughly 70% of mined output and nearly all refining capacity, producing about 270,000 tons in 2024—six times the US total. It also holds 44 million tons of reserves, more than double that of Brazil, which sits in second place (we’ll touch on this later). The US ranks seventh with just 1.9 million tons and minimal refining infrastructure. Even producers outside China often ship ore back to Chinese facilities for processing.

Washington’s Industrial Turn

The US has made a belated shift to treating critical minerals as a national capability rather than a procurement line item. The catalyst was necessity. China has tight control over mined supply and almost all global refining capacity, and at much lower costs than the rest of the world. That dominance was built over decades through state subsidies, looser environmental and labour standards, and a vertically integrated supply chain that stretches from the pit to the production line. Beijing’s willingness to ignore pollution and profitability in pursuit of control has created a refining ecosystem no market economy can replicate quickly.

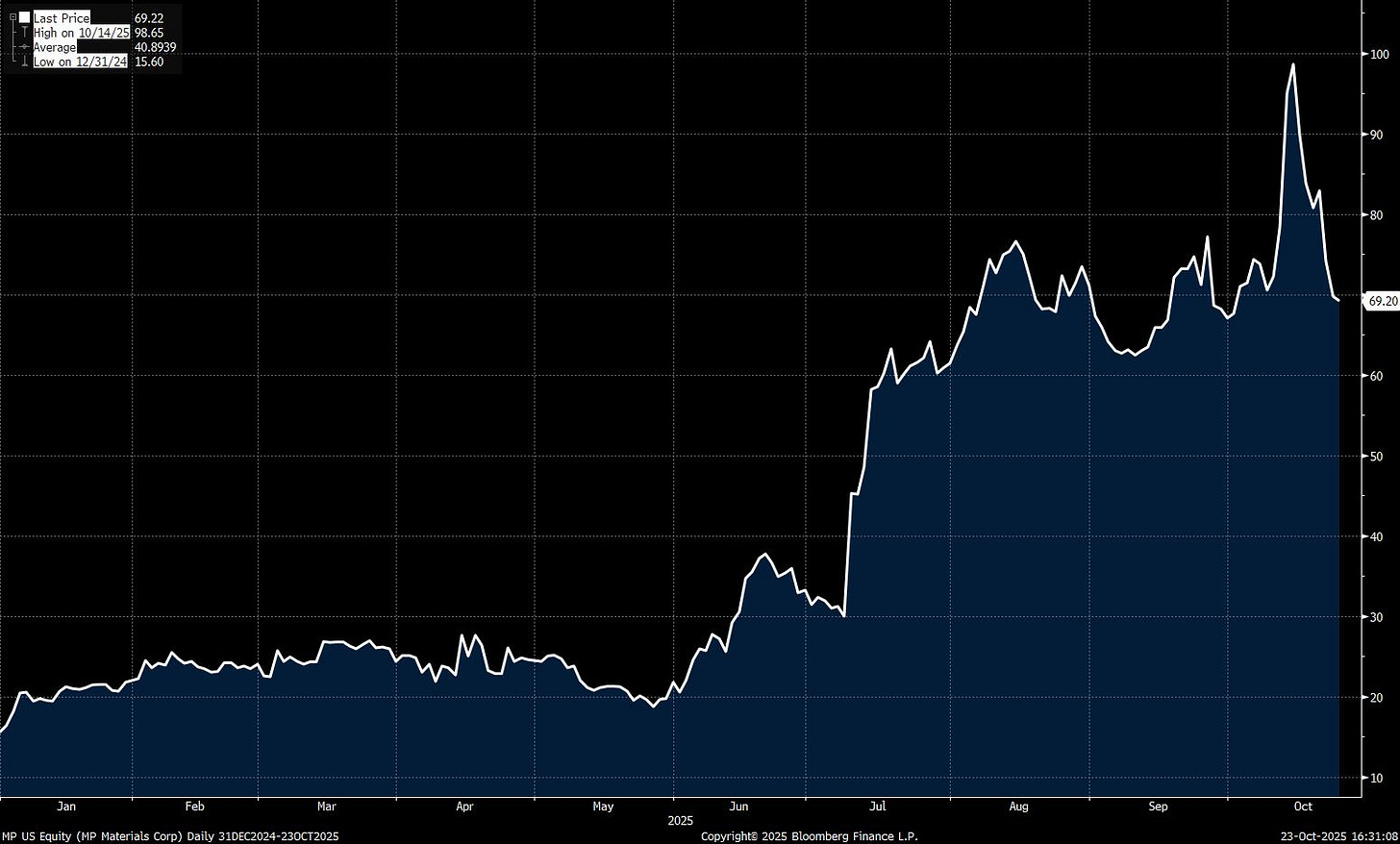

Recent export controls from Beijing on selected rare earths and magnets turned a long-standing vulnerability into a near-term constraint for Washington, and a powerful bargaining chip for China. The US response has been characteristically fiscal and bilateral: equity injections into MP Materials, offtake guarantees, and an $8.5 billion critical minerals pact with Australia to build mining and refining capacity outside China.

This marks a broader return to industrial policy. The Department of Defense’s $400 million investment in MP Materials was less about profit and more about precedent. It gave the company an equity backstop, a guaranteed buyer for magnet output, and a price floor, effectively designating MP as a national champion. Trump’s invocation of the Defense Production Act extended that approach, unlocking emergency authorities to accelerate project approvals and direct funding into extraction and processing. The Commerce Department has been tasked to assess import dependency and recommend tariffs under national security grounds.

America can’t risk dependence on Chinese refining for the materials embedded in aircraft, ships, sensors, and energy systems. Yet it also knows the limits of speed. The US currently has only one operational rare-earth mine, Mountain Pass in California, which still sends ore to China for processing. Building full refining and magnet capacity will take years and face environmental opposition.

The US is effectively buying time. Subsidies, price floors, and guaranteed demand are the fiscal equivalent of life support, keeping strategic capacity alive until the economics make sense. It’s the same playbook used in semiconductors: nationalise the risk, privatise the execution.

While the US now has an ambitious and unconventional plan to rebuild its own mining industry, it will need all the help it can get from allies if it wants to challenge China’s near-total dominance.

Australia is the Near-Term Answer

Long viewed as the world’s reliable quarry, Australia now finds itself at the centre of the West’s bid to loosen China’s grip on critical minerals. What began as a quiet trade partnership has evolved into a cornerstone of industrial strategy.

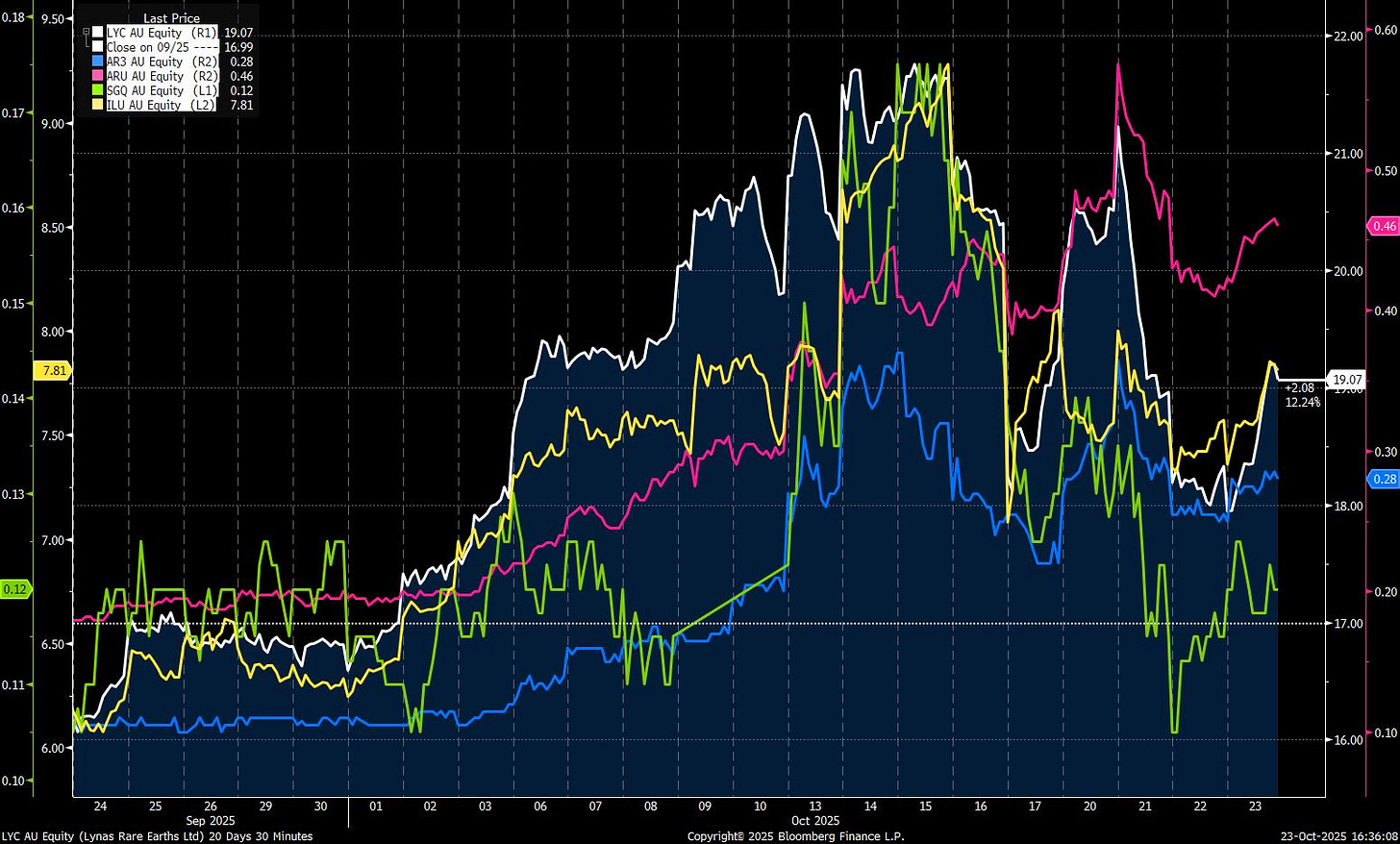

The shift became explicit with the $8.5 billion critical minerals pact signed at the White House earlier this week. The deal commits both governments to co-finance mining, refining, and magnet production, marking the first large-scale, bilateral industrial policy in the critical minerals space. It’s a recognition that the US cannot achieve mineral independence alone, and that Australia offers the scale, governance, and reliability to anchor a non-China supply chain.

For Canberra, the opportunity is as strategic as it is economic. The country holds the world’s fourth-largest rare earth reserves and is already home to Lynas Rare Earths, the only major producer and refiner of rare earths outside China. Lynas has spent years building downstream processing capacity in Malaysia and Western Australia, supplying Japan and, increasingly, the United States. Its success has turned Australia from a commodity exporter into an essential node in the allied industrial network.