When Everything Yields the Same

A convergence of yields, a divergence of risks.

Investors find themselves at a crossroads: yields across Treasurys, equities, cash, and corporate bonds have converged to strikingly similar levels. The gap between the safest and riskiest US assets is now the narrowest in four decades, a rare alignment that raises fundamental questions about where to find reward and how to measure risk.

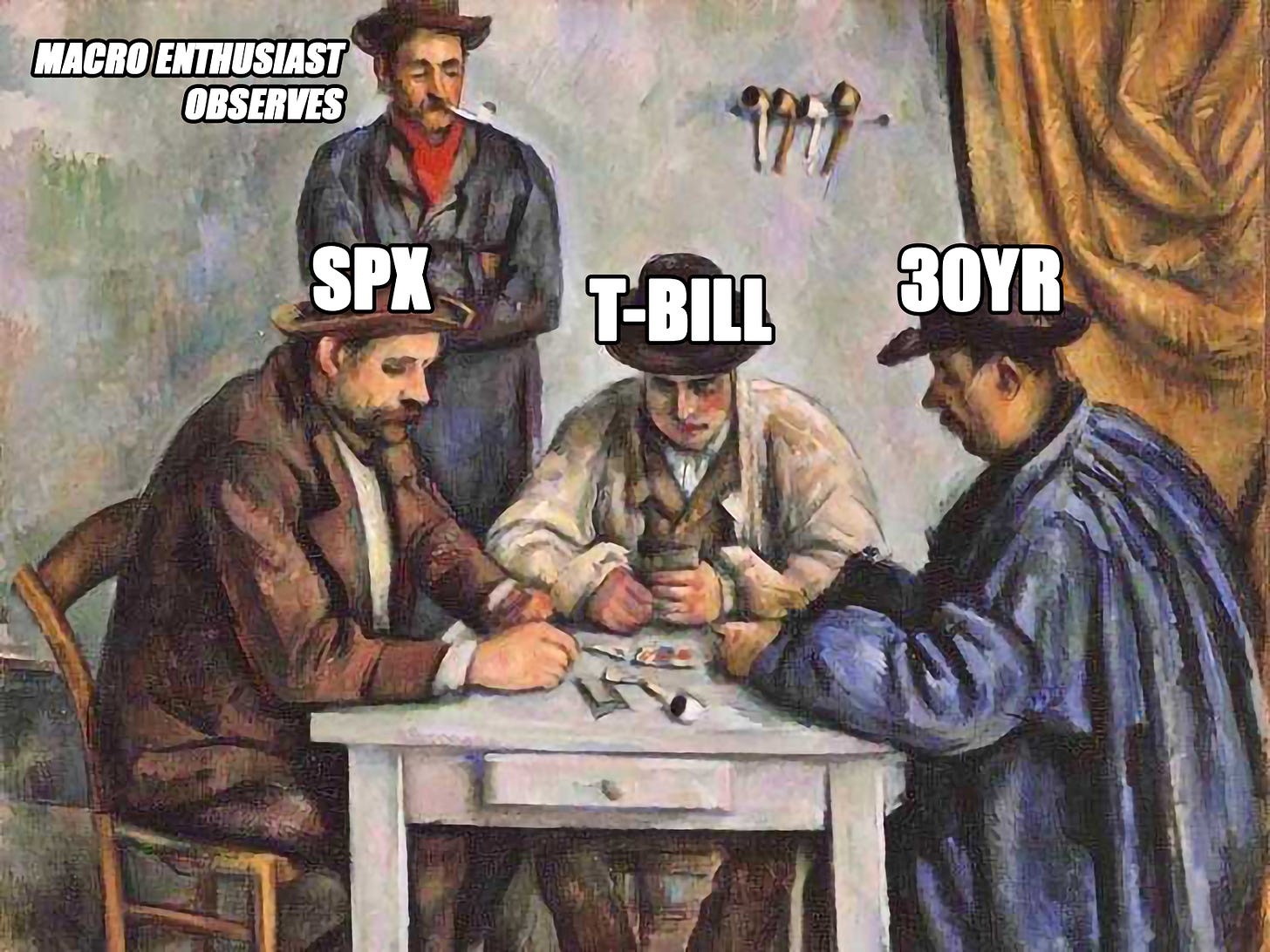

Since last November’s election, this yield convergence has persisted. It’s visible in the earnings yield for stocks (the inverse of the P/E ratio), short-term Treasury bills as a proxy for cash, and the long end of the yield curve. A decade of distortions is unwinding: inflation forced the Fed’s hand, cash and bond yields normalised, and strong corporate profits kept equity valuations elevated even as risk premiums fell.

It’s not the first time yields have been squeezed together so tightly. In the 1940s, war-driven fiscal dominance forced a ‘great compression’ in yields across the risk spectrum, only to be unwound by the surge of post-war inflation.

This levelling-out of yields has enriched those who picked the right risk assets early, riding the rally in stocks since the pandemic. But it now leaves investors with little incentive to take duration or credit risk. There’s scant reward for buying longer-dated Treasurys over money markets, or lending to corporate America instead of Uncle Sam. Stocks, meanwhile, demand a new paradigm of permanently faster profit growth to justify their slender premium over Treasurys.

Or perhaps the real story is that Treasurys themselves aren’t so safe anymore. Successive administrations have refused to tackle structural deficits, even with the economy running hot.

For Contemplation: The Great Convergence

We’re left with two questions.

First, do we really want to pay 21 times forward earnings for the S&P 500 (an earnings yield of just 4.7%) when 10-year Treasurys yield 4.4%? The margin of safety is virtually nonexistent. The same applies to the below visual of the spread between the earnings yield and the 3-month Treasury Bill. We’re betting that earnings growth will surge to fill the gap.

Granted, Wall Street forecasts of 13% earnings growth for 2026 and 2027 are nearly twice the historical norm and a sharp increase from this year’s projected 9%, and the benefits of increased AI implementation potentially support this growth. But it’s a dynamic that echoes Japan’s 1980s boom, when valuations soared on the belief that the old rules no longer applied and profits would grow forever. That story ended poorly.

Second, could the slim equity risk premium actually understate the risk in Treasurys themselves? The term premium (the compensation investors demand to lock up cash for longer) has surged to its highest since 2014. It reflects not just inflation or default risk, but volatility. Still, it’s a risk that hangs over the Treasury market.

The most commonly used metric for the term premium is the 10-year model estimate from Adrian, Crump and Moench:

Maybe the best return is not US stocks or Treasuries, but elsewhere… anywhere but America. The so-called “Abusa” trade.

This trade bypasses the US convergence altogether, hunting for yield where the real divergence still exists… overseas. Call it a “great convergence” in global growth: the US slowing, Europe and Japan reawakening. The real story, though, lies in what this convergence means for the balance of global power, and where the next big opportunity might lie.