Don't Bet Against The Greenback

Why the USD could rally into Q4.

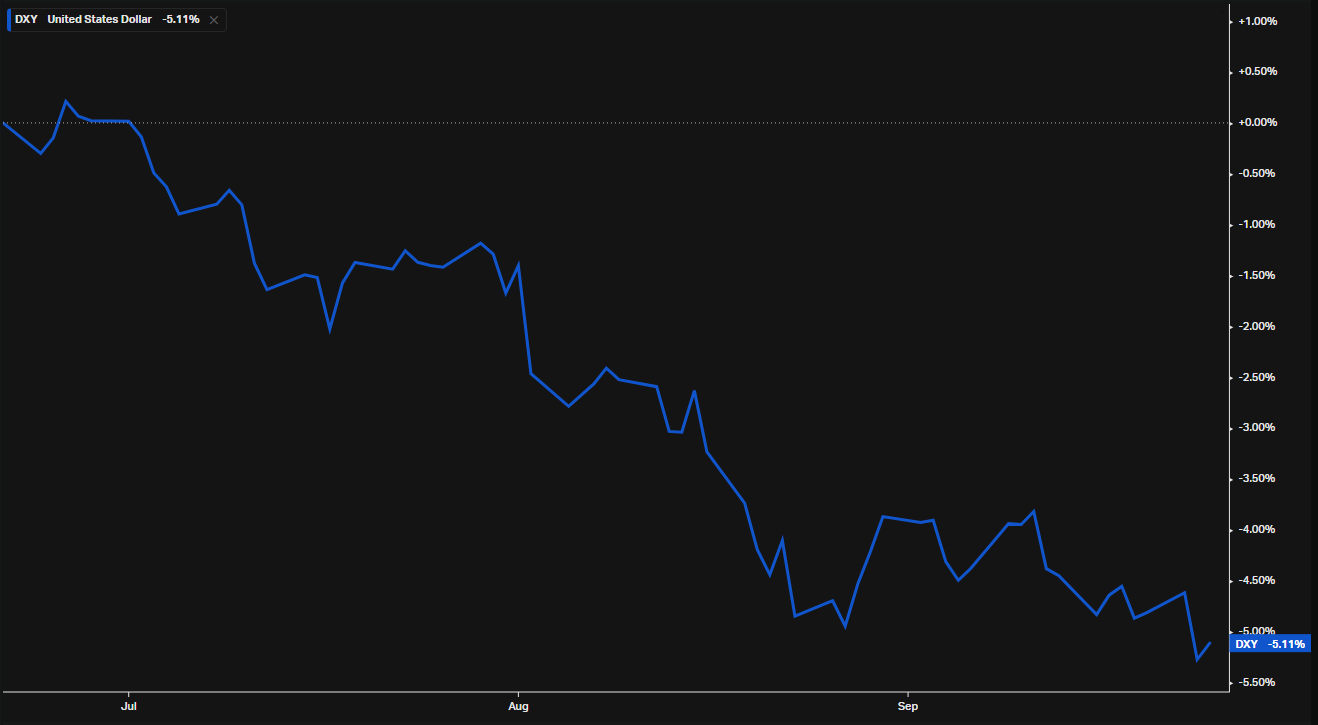

The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) printed fresh lows during September, trading at levels last seen in July 2023. For the Q3 period that we are just finishing, the index is down 5.11%.

Frequent readers of our musings will note that we have sat in the bullish USD camp for much of the summer. Although our tactical ways of expressing this in our shorter-term Monday trade ideas haven’t proven to be that loss-making, we acknowledge if we had simply entered a long on the DXY at the start of the quarter, we’d be down. The chart below shows the QTD performance.

So, is it time to throw in the towel and flip to being USD bears? We don’t think so. Let’s talk through why the index has underperformed in recent months but why the outlook is more constructive.

What is the DXY?

During this article, we’ll refer interchangeably between the DXY and the U.S. dollar. More formally, the DXY is a financial index that measures the value of the U.S. dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies.

The DXY was established in 1973 after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, which had pegged the dollar to gold. It initially started at a base value of 100.

The DXY Index is based on a weighted average of six major currencies:

Euro (EUR) – 57.6%

Japanese Yen (JPY) – 13.6%

British Pound (GBP) – 11.9%

Canadian Dollar (CAD) – 9.1%

Swedish Krona (SEK) – 4.2%

Swiss Franc (CHF) – 3.6%

A cruel summer for the DXY

Let’s start by running through a couple of the factors that have acted to pull the index lower during the quarter.

Dovish Fed Pricing

The main driver behind the weakness has been pricing in more aggressive Fed rate cuts. This knee-jerk move was compounded by a few notable data misses, such as the August payrolls report and the rise in the unemployment rate (triggering the Sahm rule).

As a result, SOFR futures picked up steam in looking for over 100bps worth of cuts for Sep-Dec FOMC meetings. Notably, the first step in monetary policy easing started to become a coin flip between 25bps and 50bps. As it happened, it was the largest of the two.

Given that one factor influencing the dollar is the relative rate differentials between other currencies, this more aggressive rate-cut pricing caused the differential to be slashed compared to most major peers. Even though the likes of the ECB, BoE, etc., have also started to cut, the path was much more shallower than the U.S.

Lack of Risk Aversion

Despite the market expecting faster-than-expected rate cuts, we haven’t seen this accompanied by significant risk aversion (which would likely be USD positive). As we’ll talk about in more detail later, we sat close to the middle of the USD smile, a place where it weakens.

For much of the quarter, global growth has been okay. Risk sentiment has been positive, causing global equities to outperform, with major U.S. indices recording consecutive all-time high closes.

Yet U.S. growth hasn’t been outperforming the rest of the world (RoW), nor have we been in a situation where U.S. growth has been so slow that investors have been pivoting and buying USD as a risk hedge.

US Election

The election is now coming very much into view, and we feel that the first election factor, namely the risk premium, supports a dollar rally. The risk premium we speak of here is a Trump victory. There are four possible outcomes from the election: a red wave, a blue wave or a divided congress case for either.

In our view, a Harris blue wave is unlikely, whereas the main slant is either a Democrat-divided congress (circa 50% prob), which is long-term USD neutral, or a Trump-divided or Trump red wave (30% prob). These two outcomes are strongly USD positive. So in advance of any result, it makes sense for some positioning to place a risk premium on the Trump scenarios, effectively bidding up the dollar in the run-up between now and November.

Let’s say Trump does gain a majority. The main driver behind USD strength into year end and beyond stems from his policies around trade tariffs.

Trump has proposed tariffs on a broad range of imports, possibly ranging from 10% to 20% for most goods and up to 60% for certain Chinese products. He has previously suggested imposing tariffs on imported oil, which could raise gas prices in the U.S. by up to 5% due to the heavy reliance on imported crude oil for specific refinery needs.

Additionally, Trump has indicated that he may use tariffs as leverage in trade negotiations with countries like Mexico and Canada. He has also discussed tariffs as a way to counteract what he believes to be unfair foreign trade practices.

As for the impact on the currency, studies in the past show that the countries imposing the tariffs tend to see their currency appreciate in value. This also can be noted from the likely inflationary pressures that these higher import prices would bring, helping to lift the short end of the yield curve.

Over the space of the years to come, the USD view becomes a lot more murky when talking about this element in particular. Do tariffs work and contribute to a net increase in economic growth for the country imposing them? See below…

Now, let’s pivot back to a case of either party winning the election. Both are looking to implement expansionary fiscal policies. We’ve had Trump advocate for lower corporate tax rates and defence spending. Harris will likely continue the large-scale infrastructure spending that Biden put in place, alongside pledges for spending in energy and education.

Again, both of these outcomes are likely USD-positive, driven by the inflationary pressures triggered by such spending plans. As a side note, if these measures are taken by the market to be growth-positive, i.e., good for the economy, it could fuel a larger USD bid. However, if the spending is seen as being wasteful in some areas, or pointless, this would hamper gains.

Hard Landing vs Soft Landing

The market seems fairly happy that US policymakers will be able to engineer a soft landing over the coming year:

You might think it odd that we’re talking about anything but the possibility of a soft landing, but consider a couple of points on this that was flagged up by the team behind The Kobeissi Letter in a thread on X last week.

They flagged up the below Bloomberg chart that shows the mid-1990s were the only time that the Fed was able to achieve a "soft landing."

“When comparing 2024 to 1995 (the only soft landing), we are in a vastly different economic backdrop. The economy is recovering from the pandemic after 10% inflation and the fastest rate hike cycle in history. And unemployment is still relatively low.

The situation in 1995 was the exact opposite. In early 1994, the economy was approaching its third year of recovery following the 1990-91 recession. By February 1994, the unemployment rate was falling rapidly, down from 7.8% to 6.6%. CPI inflation sat at 2.8%, and the federal funds rate sat at around 3%.”

Now look, this argument can be put over on both sides, but we’re focusing today on the impact on the USD. Simply put, we think either scenario acts as a positive. This is down to the function of the USD smile (see below).

A hard landing likely sees a recession, and as we all know, ‘when the US sneezes, the whole world catches a cold.’ The knock-on impact of lower consumer sentiment, restricted credit, higher unemployment, etc, would feed through to trading partners. As a result, the dollar likely becomes bid as investors go to it as a safe haven (the left side of the smile).

If a soft landing occurs, then we’re expected to be happy, cheer and admire the Patriots. In this case, there’s a case for saying that US growth could outperform the rest of the world (RoW), pushing it higher as it climbs to the right hand side of the smile.

The risk to this view is the middle part, which is what we’ve been experiencing for the summer.