Drawing The Line of Independence

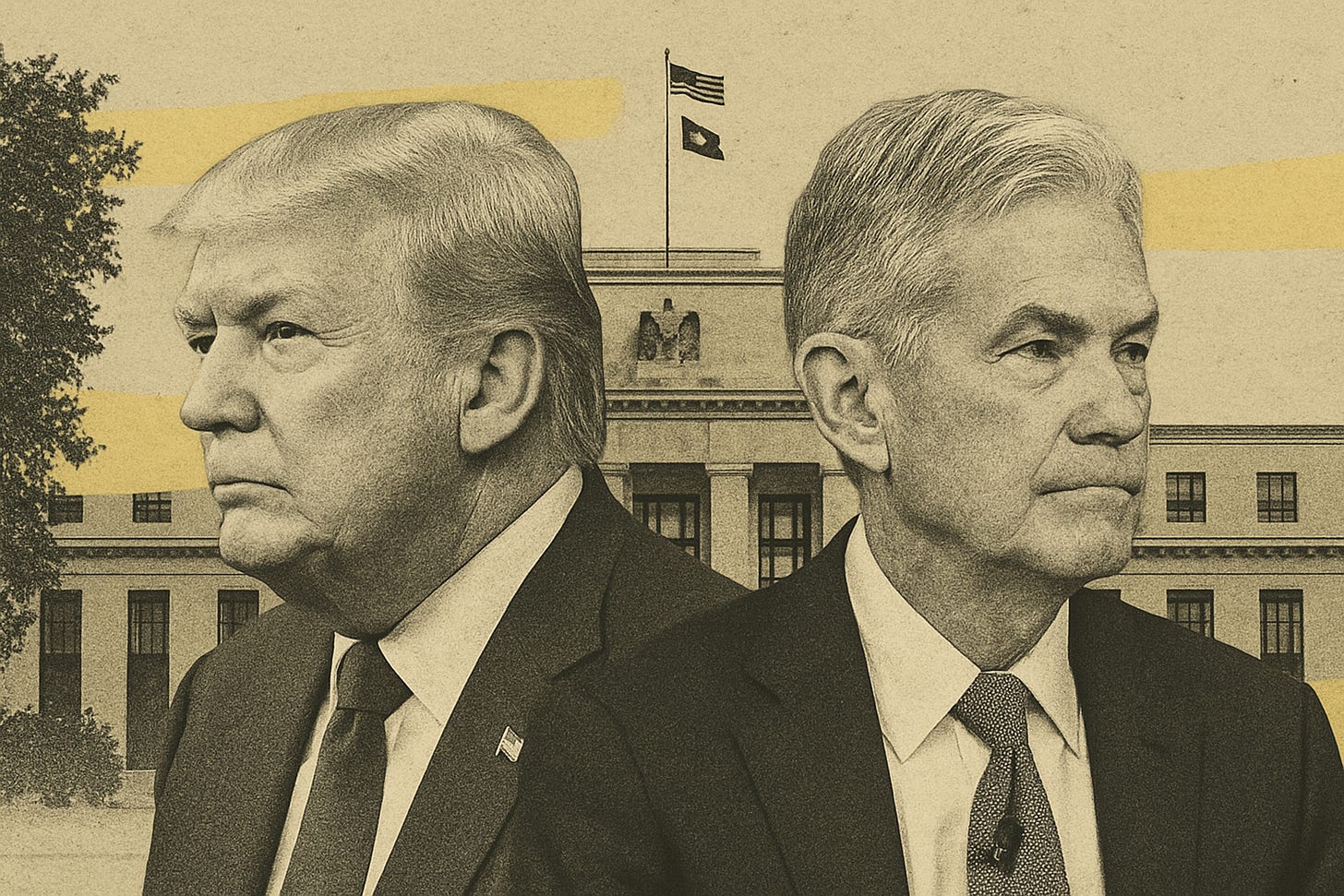

Trump vs Powell.

On April 10th, a headline crossed the tape that, in a calmer week, might have dominated the discourse. However, markets weren’t calm. Trump had just hit pause on tariffs, volatility was ripping through the rates complex, and the bond market was flashing stress signals. The story got lost in the noise.

But markets have a short memory and a sharp instinct for relevance. With this week offering little in the way of fresh headlines, attention circled back to what was missed. What had once been a footnote now feels more like a front-page showdown.

The headline in question didn’t just ask who leads the Fed. It raised a more fundamental set of questions: To what extent can a president shape the direction of U.S. monetary policy? What happens when political pressure collides with institutional design? And what are the consequences if the Fed’s independence starts to crack? In the days since, the topic has gained traction, with analysts, economists, and market participants all weighing in. What began as a speculative thread is quickly becoming a broader macro conversation. And if it continues to gather momentum, it won’t remain a constitutional curiosity—it’ll start showing up in the price.

The Boundaries of Independence

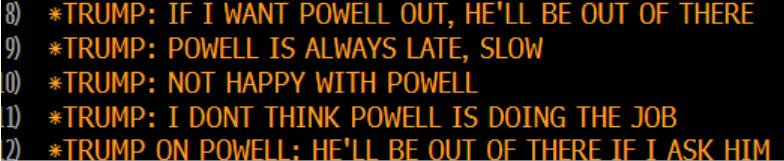

Trump is turning his attention from shaking up global economic balance and relations to shaking up America’s internal economic structure, questioning the Fed’s decision-making, and calling on the central bank to lower interest rates. The week’s events revived a refrain from his first stint in the White House.

At the heart of this debate is a simple but unresolved question: how much control does a president actually have over the Federal Reserve? The legal answer is murky. The political answer depends on willpower and timing.

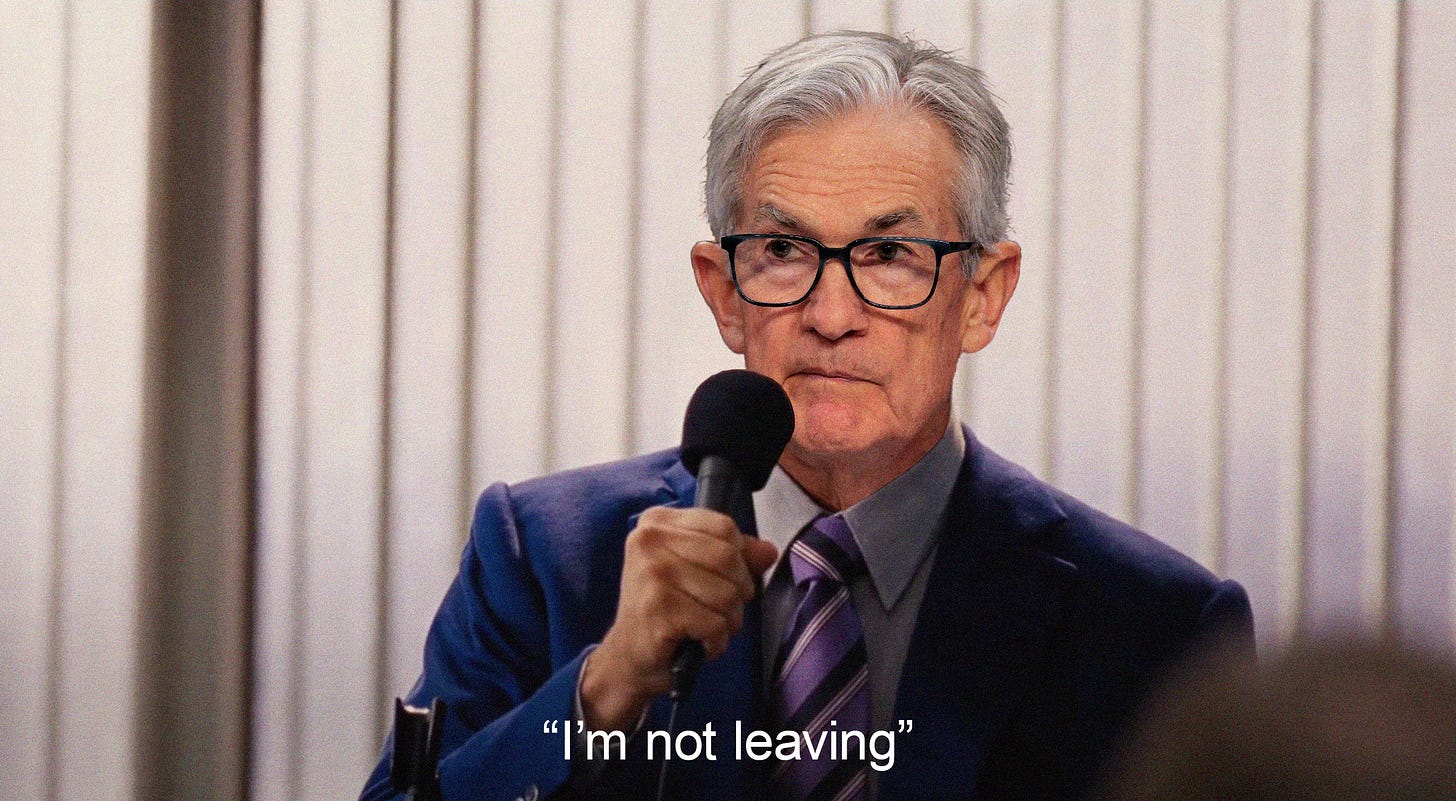

Trump once floated removing Jerome Powell in 2018, a move that tested the boundaries of the Federal Reserve Act. The law allows a president to remove a Fed Governor “for cause,” but what constitutes “cause” has never been litigated in this context. Removing Powell as chair, rather than as a governor, might sit in a legal grey zone, but even then, he would retain a seat on the Board and likely continue leading the FOMC. In other words, removing the figurehead may not remove the influence.

That’s why legal scholars and Fed watchers have started paying closer attention to the broader legal campaign. The Trump administration has made clear its intent to challenge Humphrey’s Executor, the 1935 Supreme Court case that protects independent agencies from political purges. If that precedent is overturned, the dominoes could fall, giving a future president significantly more control over regulators, including the Fed.

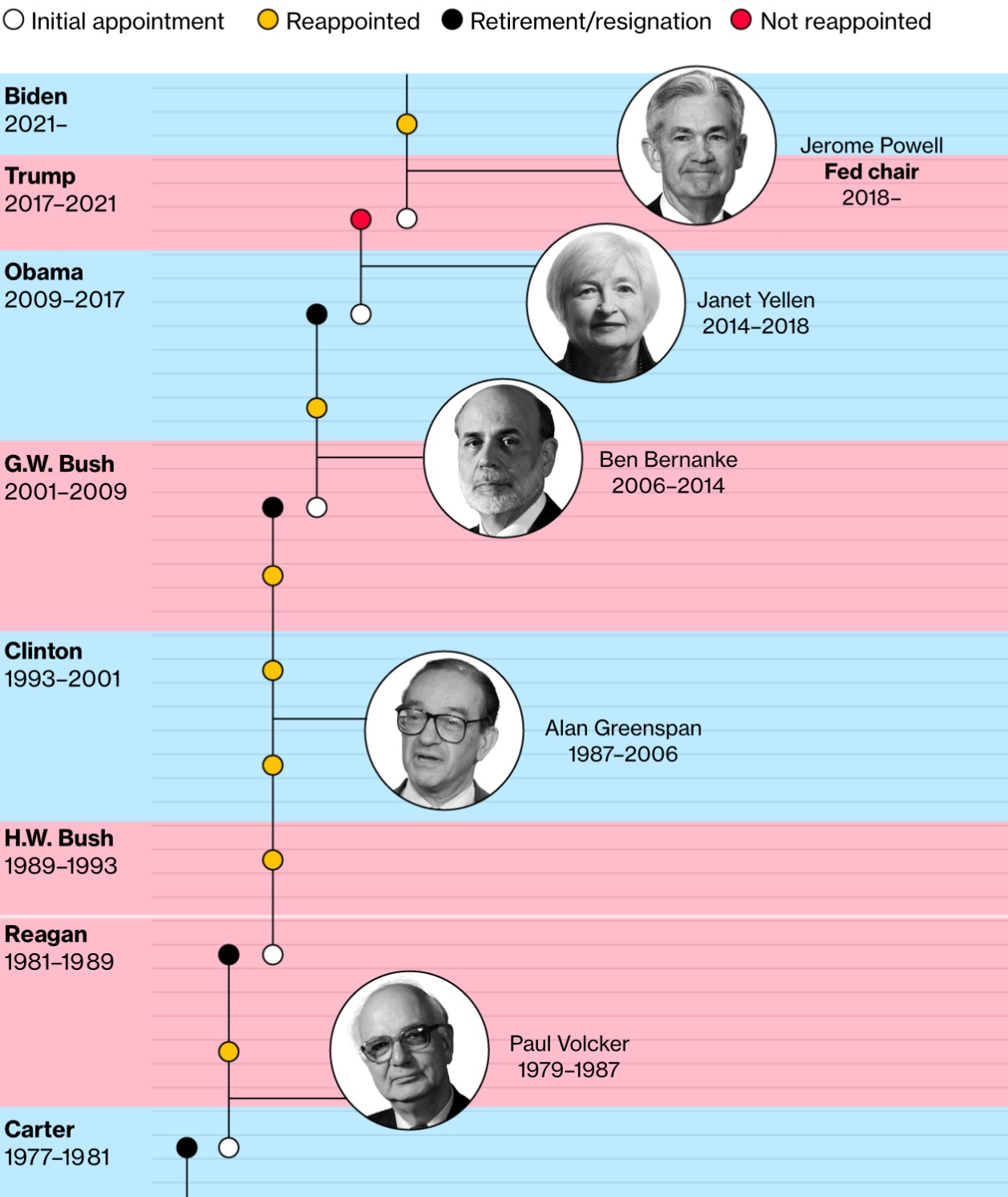

For now, the most straightforward power a president holds over the Fed lies in appointments. Trump will have opportunities. Powell’s chairmanship expires in 2026, and Governor Kugler’s term ends that same year. But even full control of the Board of Governors would only go so far. Regional Fed presidents, who also vote on policy, are appointed through a separate process, insulated from the White House.

Still, Trump has shown a willingness to test limits. His selection of Michelle Bowman for Vice Chair for Supervision—a key regulatory role—came on the heels of Michael Barr’s resignation, amid speculation that pressure was mounting from above. It’s a playbook we’ve seen before: find the legal opening, apply political pressure, and let institutional norms do the rest.

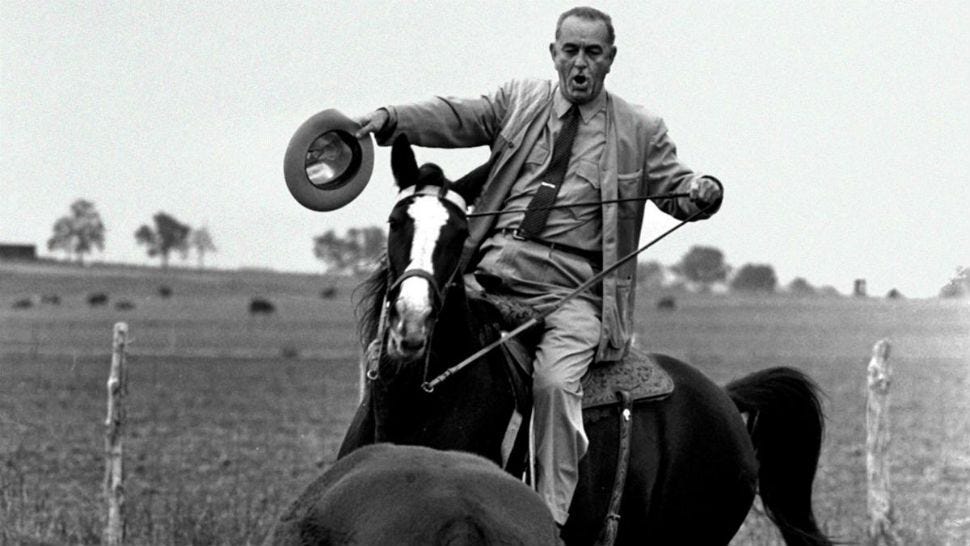

Of course, the formal channels aren’t the only levers of influence. Presidential pressure campaigns have a long pedigree. From Lyndon Johnson dragging the Fed chair to his Texas ranch, to Nixon leaning on Arthur Burns, history is full of moments where the Fed’s supposed independence bent under political weight. Trump is more direct, airing his frustrations publicly, lambasting the Fed’s rate decisions, and using executive orders to chip away at the walls separating the central bank from the Oval Office.

And it’s not just Trump. The machinery around him is aligning for a broader assault on bureaucratic independence. Elon Musk’s “DOGE” department, a technocratic tool of political disruption, is reportedly scrutinising the Fed’s staffing and operations. The Federal Reserve may be legally self-funded and physically separate from other agencies, but the political climate is starting to encroach on that insulation.

For his part, Powell continues to affirm the Fed’s apolitical mandate. But in an environment where everything is political, that stance may be increasingly difficult to defend. Independence is no longer just about keeping distance from the White House; rather, it’s about surviving in a system actively being redesigned to eliminate such distance altogether. Powell addressed some of these points in an interview earlier this week:

Bessent’s Role as Mediator

At the core of the modern central bank model lies a basic tension: what’s good for politicians in the short term often runs counter to what’s necessary for the economy in the long term. Cheap money fuels growth, jobs, markets… and votes. But over time, that same medicine can distort prices, stoke inflation, and erode financial stability. That’s why central banks were granted independence in the first place: to say no when the political impulse is to say go.

The credibility of the Fed rests not just on its models or forecasts, but on the perception that it’s willing to make unpopular decisions; that it can hike into an election year, that it can tighten when growth slows, that it answers to the data, not the party in power. Break that perception, and the whole framework starts to wobble—not just in Washington, but across every asset class that prices off future expectations.

Even within Trump’s own orbit, there’s recognition of that fragility. His Treasury secretary, Scott Bessent, called Fed independence a “jewel box that has got to be preserved.” The irony is hard to miss: a campaign openly signalling intentions to reshape the Fed’s leadership while praising the virtues of restraint. Whether that’s a hedge, a warning, or just political posturing remains unclear. But in markets, clarity matters. And right now, the message is anything but.

According to two people close to the White House granted anonymity to share details of private discussions, Bessent has cautioned White House officials on numerous occasions that any attempt to fire Powell would risk destabilising financial markets. Don’t forget, Bessent says he has breakfast with Powell once a week, highlighting the ties between the two.

One way that Bessent can actively help to calm the situation is regarding getting everything in line to start interviewing candidates for the next Fed chair, which is due to start in the fall for the changing of the guard in May 2026. If Bessent can put Trump’s focus on dealing with the next Chair, rather than going after the current one, it could help to see Powell out by diverting attention.

Historically, the changing of the post hasn’t been a political hot potato to the same extent as it is currently. Alan Greenspan was appointed by different Republican and Democratic presidents. Bernanke was appointed under Bush and reappointed under Obama during the tricky GFC period.

The EM-ification of America (parallels to Turkey)

The story of a central bank losing its independence under political pressure is not new. But it’s a story markets are more accustomed to hearing in emerging markets, not in the world’s largest economy.

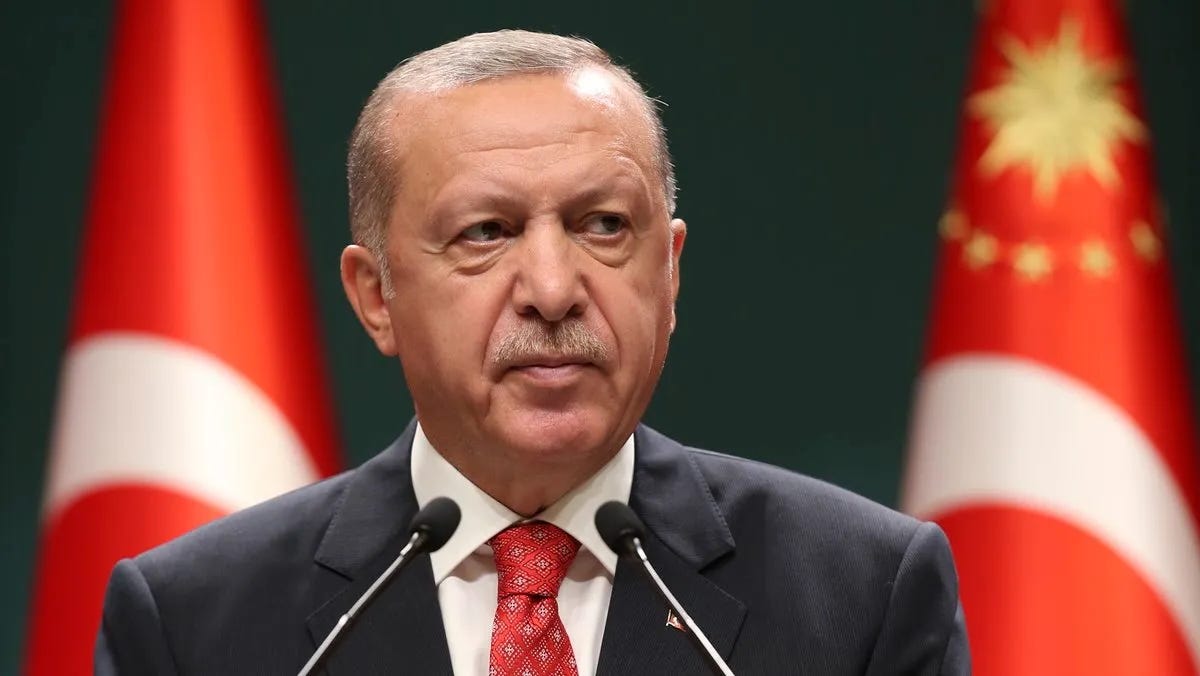

Take Turkey. Over the past decade, the credibility of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) has been steadily dismantled, largely due to sustained interference from President Erdoğan. His unorthodox view (that high interest rates cause inflation) led to a series of policy interventions that flew in the face of conventional economics.

The tipping point came when Erdoğan began firing CBRT governors who resisted his directives. This wasn’t a one-off. It happened in 2019, again in 2021, and once more in 2023. Each dismissal sent a clear message to markets: monetary policy was no longer being set independently but by political fiat. The results were predictable: delayed rate hikes, collapsing investor confidence, a tanking currency, and entrenched inflation.

The comparison to the U.S. isn’t perfect and shouldn’t be overstated. But if presidents begin removing governors of independent agencies simply for dissenting, the distance between Washington and Ankara narrows more than most would like to admit.

The consequences of eroding central bank credibility are not theoretical. Turkey’s experience shows how quickly investor capital can flee when monetary independence is compromised. Even with recent attempts to return to orthodoxy, the CBRT still carries the scar tissue of political overreach. The Fed, and by extension the U.S. financial system, cannot afford to walk that path.

Where We Stand

Much of the recent discourse has zeroed in on Powell, whether he’s too hawkish, too slow, or simply out of touch with the political moment. There’s been plenty of talk about firing him to force rates lower and bringing someone more dovish and loyal to Trump. But far less attention has been paid to a basic fact: Powell doesn’t set policy unilaterally. The Fed is a committee—nineteen policymakers, a range of views, a deliberative process. Removing the chair doesn’t replace the institution.

And even if one disagrees with Powell’s stance (holding rates steady in the face of slowing growth, wary of reigniting inflation), the alternative being floated is far worse. A Fed that is bent to the will of the presidency, shaped by short-term political incentives, and stripped of its independence would do lasting damage not just to its credibility, but to the global perception of the U.S. as a steward of stable policy.

Markets may be forward-looking, but are also deeply sensitive to institutional integrity. Undermine that, and the cost won’t be limited to press conferences and talking points; it will be reflected in risk premia, capital flows, and eventually, in the economic outcomes those seeking control claim to protect.

The Powell-Trump tension is real. But the greater risk isn’t who’s in the chair. It’s who gets to decide how the chair behaves.

AP

It wouldn’t surprise me at all if Trump declares he’s firing Powell. It also wouldn’t surprise me to see the 10 year shoot up 50 or more bps that day. The only thing worse than an insulated government committee setting rates is politicians setting rates.

GM