Ghosts of Price Wars Past

From Jakarta to Riyadh, the echoes of oil wars shape today's market.

In oil markets, it is rarely strength that sets the great conflicts in motion. Price wars often begin as acts of desperation, cloaked in bravado, symptoms of deeper economic and political fragilities. The ghosts of 1998 and 2020 haunt the decisions made by today’s energy leaders, even when they dare not speak their names.

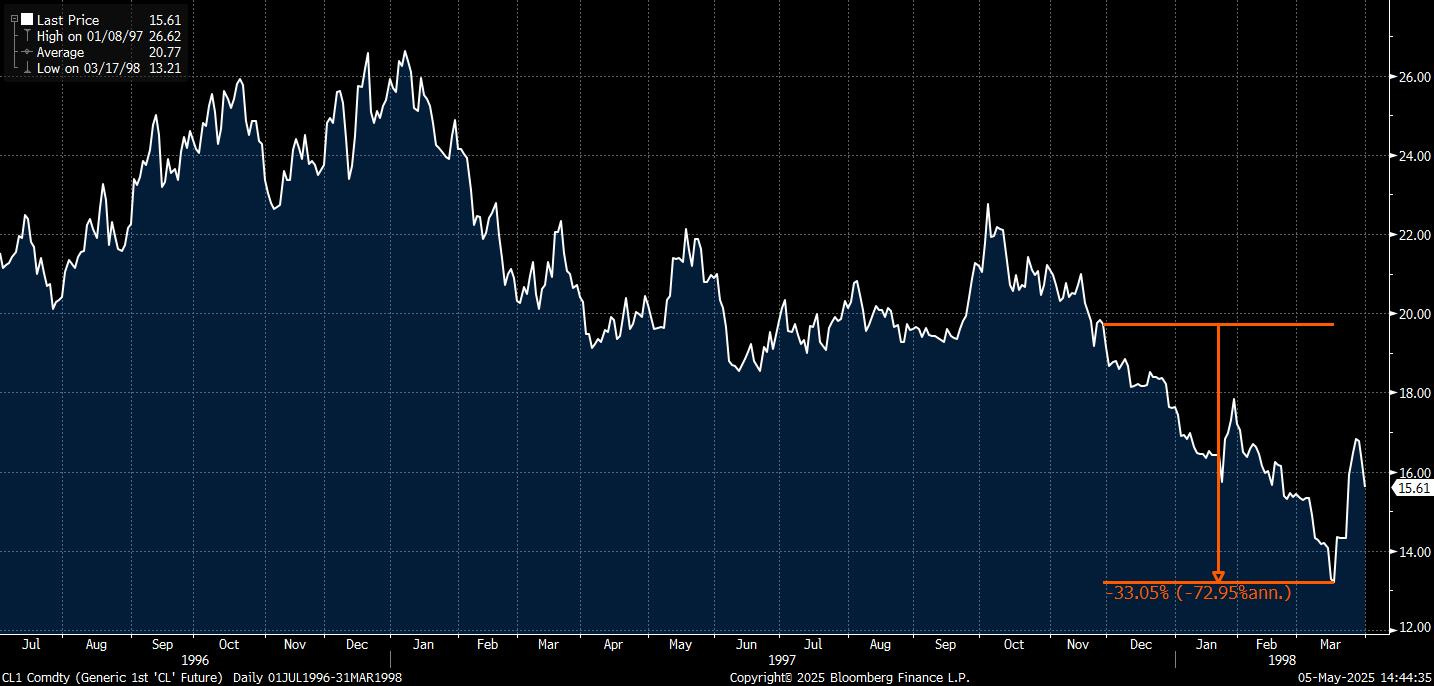

The memory of Jakarta still looms large. In late 1997, as the embers of the Asian financial crisis spread, OPEC gathered in Indonesia and, in a moment now seared into cartel folklore, voted to raise production. Indonesia’s own rupiah was in freefall that very week, but the scale of the contagion was underestimated. OPEC had aimed to defend its market share, assuming that emerging market demand would absorb the extra barrels. Instead, collapsing Asian economies gutted consumption, just as new supply flooded the market. Within a year, oil had plunged below $10 a barrel, a collapse so severe that it reshaped the architecture of OPEC’s internal politics for a generation. The mistake was not simply one of timing, but of hubris: a belief that the economic cycle could be overridden by cartel discipline alone.

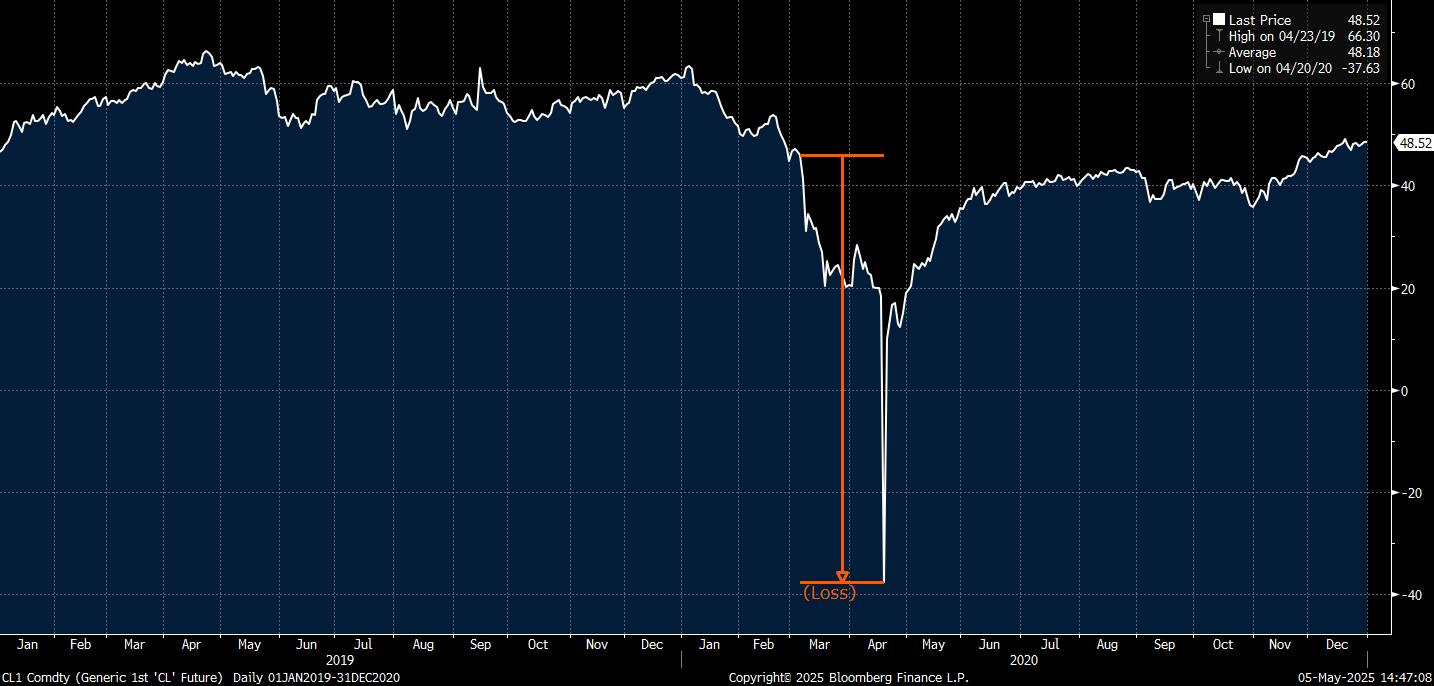

Two decades later, in early 2020, another price war erupted, this time with Saudi Arabia and Russia at its centre. As COVID-19 began to tear through global demand, OPEC+ leaders met to discuss deeper production cuts. Russia refused, calculating that lower prices would be survivable and even advantageous. Riyadh responded with a nuclear strike: slashing official selling prices, boosting exports by hundreds of thousands of barrels per day, and unleashing a flood into a market already buckling under lockdowns. Storage filled, futures collapsed, and oil traded below zero—an unprecedented rupture. It was a war designed to maximise pain quickly, and it succeeded. Within 35 days, capitulation was achieved, and a new, uneasy truce was brokered.

These episodes are not simply historical curiosities; they are warnings. Both conflicts began from a misreading of underlying weakness (a demand shock in 1998, a pandemic in 2020). Still, both were catalysed by the same fundamental instinct: to impose discipline through force, sometimes on rivals within OPEC and sometimes on external threats like U.S. shale or Russia. The method shifts, but the impulse endures.

Recent moves by Riyadh carry echoes of both eras, but the strategy has evolved. This is not a repeat of the indiscriminate bombardments of the past. Instead, Saudi Arabia is wielding the scalpel, not the hammer—applying pressure precisely where the cartel’s fractures are most exposed, allowing weakness to fester rather than forcing a swift collapse. Production is being nudged higher, rogue oil producers (Kazakhstan, Iraq and the United Arab Emirates) are being isolated, and, crucially, no serious attempt is being made to prop up sentiment with optimistic headlines. The message is implicit but clear. Saudi Arabia can live with lower prices for longer than its rivals can.

If the surface tactics are different, the deeper forces remain familiar. Demand expectations, inflated by hopes of a soft landing, are vulnerable. Global economic risks are multiplying. Beneath the strategic manoeuvring lies a simple truth: the centre of gravity in the oil market is shifting once again, and the adjustment will not be painless.