Global Primer Series: Cross Currency Basis

Understanding the systemic foundations of the cross-currency basis trade.

Contributions from Mark Rogerson, EMEA Head of Rates Products at CME Group.

For decades, global financial markets have relied on the seamless flow of capital across borders. But beneath the surface of currency exchange lies a crucial yet often overlooked mechanism: the cross-currency basis. This spread, which reflects the cost of swapping one currency for another via the short-term funding markets, serves as a barometer of global liquidity, central bank policies, and financial system stress.

At its core, the cross-currency basis represents the difference between the implied interest rate from FX swaps and standard interbank rates. In theory, arbitrage should keep this spread near zero, but in reality, it fluctuates due to market imbalances, funding pressures, and shifts in monetary policy. These distortions create opportunities for sophisticated traders (banks, hedge funds, and asset managers) who exploit the basis for arbitrage, hedging, and macro positioning.

Whether it’s a Japanese institution seeking dollar funding, a European bank hedging its balance sheet exposure, or a hedge fund capitalising on dislocations, cross-currency basis trading is a critical yet complex field. This primer explores the mechanics of cross-currency basis swaps, the forces that drive them, and the trading strategies employed by market participants. Understanding these dynamics isn’t just about theory—it’s about navigating the interconnected world of global finance, where liquidity mismatches and central bank interventions create both risk and opportunity.

This primer runs through:

- Cross-Currency (XCCY) Basis Swaps

- Key Participants in the Market

- Drivers of XCCY Basis Movements

- Liquidity and Market Structure

- Trading Strategies

- Behavioural Aspects and Market Psychology

(If you’re into FX, great. If you love macro plumbing and balance sheet nuance, even better. If none of this makes sense yet, no stress. Read it twice. You’ll get there.)

Understanding Cross-Currency (XCCY) Basis Swaps

Cross-currency basis swaps (XCCY swaps) are about solving a problem: how do institutions safely and efficiently borrow in one currency while holding assets or funding needs in another?

These swaps are essential plumbing in the global financial system—used daily by banks, insurers, corporates, and sovereigns to manage currency mismatches in funding, hedging, and investing. But while the concept sounds straightforward (swap one currency’s cash flows for another’s), the structure carries important nuances.

Initial Exchange (Notional Swap at Spot):

At the outset of a cross-currency basis swap, the two parties exchange notional principal amounts in their respective currencies. For example, a Japanese bank might lend ¥10 billion and receive $75 million in return (based on the spot USD/JPY rate). This exchange is not just a pricing reference, but a physical currency exchange. Each party takes possession of the other’s currency, which they can use to fund loans, invest, or meet liquidity needs.

This is what distinguishes XCCY swaps from pure FX derivatives like Forward outrights, futures or options. The cash actually moves. It’s real balance sheet funding, not just a bet on exchange rates.

Periodic Interest Payments:

Once the initial notional is exchanged, each side pays interest to the other on the received currency. This is typically done quarterly or semi-annually, with the floating rate linked to local interbank benchmarks1. Each counterparty essentially pays what it would have to pay if it had borrowed the foreign currency outright. But here’s where the “basis” comes in: one leg (usually the non-USD leg) includes a spread, called the cross-currency basis.

This basis is either added to or subtracted from the floating rate. Example: If the EUR/USD basis is –25 bps, the EUR leg pays EURIBOR –0.25% and the USD leg pays straight SOFR.

This negative basis reflects the fact that borrowing USD via the swap is more expensive than borrowing EUR. The negative spread is effectively a “premium” that non-USD institutions pay to access dollar funding in the swap market.

Final Exchange (Reversing the Initial Notional):

At the end of the swap’s term (say 3 months, 1 year, or longer), the original notional amounts are re-exchanged using the same spot FX rate from the contract’s start.

This symmetry is key. It means the transaction is not exposed to FX risk from start to finish, assuming both parties hold to maturity. The floating interest rates may fluctuate, but the principal reverts to its original state, making the swap an efficient funding or hedging tool.

The Cross-Currency Basis:

The basis itself (often quoted in basis points) is a market price that reflects real-world frictions and imbalances. In a perfectly functioning global market, where capital flows freely and there’s no credit or regulatory friction, the basis should be zero. This is the world of covered interest parity (CIP)—a foundational principle of FX markets.

But in practice, the basis is almost never zero, as several factors can weigh in (more on these later). Think of the cross-currency basis as a market barometer—it tells you not just about relative interest rates, but about funding stress, liquidity demand, and institutional preferences across the world.

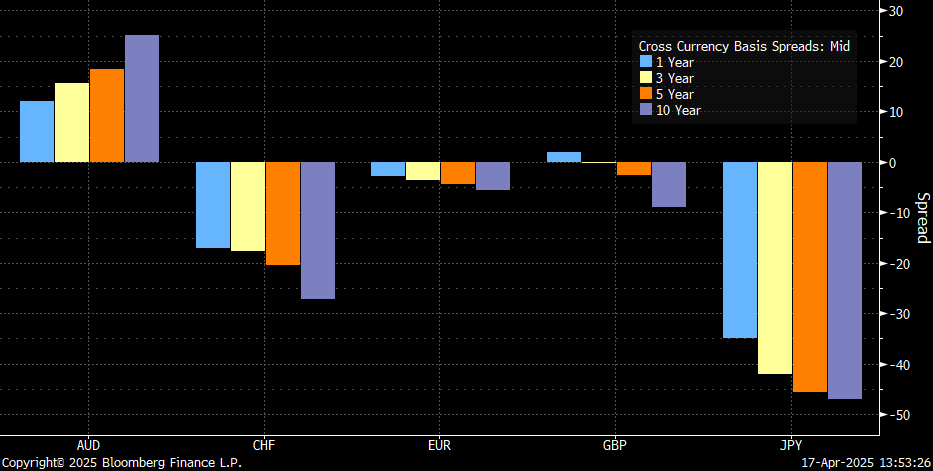

Below shows the current basis spreads for selected major currencies versus the USD across a range of tenors:

XCCY Basis Swaps In Comparison To Other Derivatives

Versus FX Swaps:

Some might initially get confused when comparing XCCY basis swaps with more traditional FX swaps. Both involve the exchange of notional amounts in different currencies at the start and end of the contract. However, the key distinction lies in how interest exposure is managed. In an FX swap, interest rate differentials are implicitly embedded in the forward FX rate—so while you only exchange principal at the start and end, the relative value of those cash flows effectively hedges the interest differential between the two currencies.

By contrast, cross-currency basis swaps explicitly incorporate periodic interest payments throughout the life of the contract, typically on a quarterly or semi-annual basis. This allows for a more granular hedge of both principal and interest rate exposure, and also reduces counterparty credit risk, since exposure is reset regularly rather than accumulated until maturity. Basis swaps are commonly used for longer-dated funding and hedging, though they are not exclusively limited to long tenors.

In short, if you’re hedging short-term FX risk or forward cash flows, an FX swap may suffice. But for multi-period, full exposure hedging of both currency and interest rate risk, the XCCY basis swap offers a more complete and efficient solution.

Versus IR Swaps:

Standard interest rate swaps (IRS) only let you manage the cash flows within the same currency. Although you swap the principal and the cash flows over the tenor of the contract, you can’t hedge foreign currency risk or enter the contract with differing currency legs. Therefore, if a company wants to hedge FX risk and align cash flows across different currencies, the XCCY basis swap is the best choice.

How To Interpret the Spread

Let’s say you’re a European corporate CFO and want a one-year EUR/USD XCCY basis swap. Data shows that the basis is negative -2.875bps:

What does this mean? Simply put, a European borrower entering into a EUR/USD cross-currency basis swap to obtain dollars will not pay more than the market USD interest rate (SOFR) directly. Instead, they will receive less than the prevailing EUR market rate (e.g., EURIBOR) on the euros they lend into the swap—in this case, 2.875 basis points less. Functionally, this reduced return on the euro leg reflects a premium paid for accessing USD funding via the swap, even though the USD leg pays the standard market rate. While economically similar to paying an extra 2.875bps on the USD borrowing, it’s technically expressed as a discount on the return for the non-USD leg.

A negative basis is quite common today, reflecting the historical trend of demand for USD (more on this later).

Key Participants in Cross-Currency Basis Markets

A range of financial players engage in cross-currency basis trading, each with different objectives:

Corporations & Multinationals: A part of the market relates to the corporate space. Corporations often find it cheaper to borrow in their home currency, so let’s present a scenario where a U.K. business wins a U.S. project and now needs to fund it for the coming couple of years. It can raise debt in GBP, then enter a XCCY swap for USD for this time period. This provides the USD funding, on which it will pay SOFR + the basis. It’ll receive GBP SONIA for the period, and at maturity, revert the USD back to GBP, where it can look to pay off the debt in local currency.

Banks & Dealers: Act as intermediaries, providing liquidity in swaps while managing their own funding needs. For example, in the corporate scenario above, a bank desk would take the other side of the trade. Given the OTC nature of these trades, the company would want to deal with one of their main banking partners to facilitate such a deal.

Hedge Funds & Proprietary Traders: Funds can lower their cost of capital by tapping into cheaper funding markets through cross-currency swaps. They often use these instruments to implement currency-linked arbitrage or funding strategies, taking advantage of small mispricings with leverage. Because the basis swap markets are deep and liquid, particularly in major currency pairs, hedge funds frequently use them for short-term relative value trades or to express macro views. In addition to arbitrage, hedge funds may also take speculative positions on the basis itself. During times of market stress, there is often an acute demand for USD liquidity, which causes the cross-currency basis to move sharply more negative. Funds that anticipate this dynamic may position early, paying the basis ahead of dislocations, or receiving it as a mean-reversion trade once central banks intervene or the stress fades.

Sovereign Wealth Funds & Pensions: Manage currency exposure on global investment portfolios. Although these funds are less speculative than prop traders or hedge funds, they are still a key part of the market given the notional size traded when trying to hedge.

Central Banks: Monitor and intervene in FX markets to ensure stability, particularly during crises. For example, at the start of the pandemic the Fed reactivated and expanded its swap lines with major central banks, allowing them to access USD directly from the Fed and lend to their own banks, massively improving dollar liquidity.

Drivers of XCCY Basis Movements

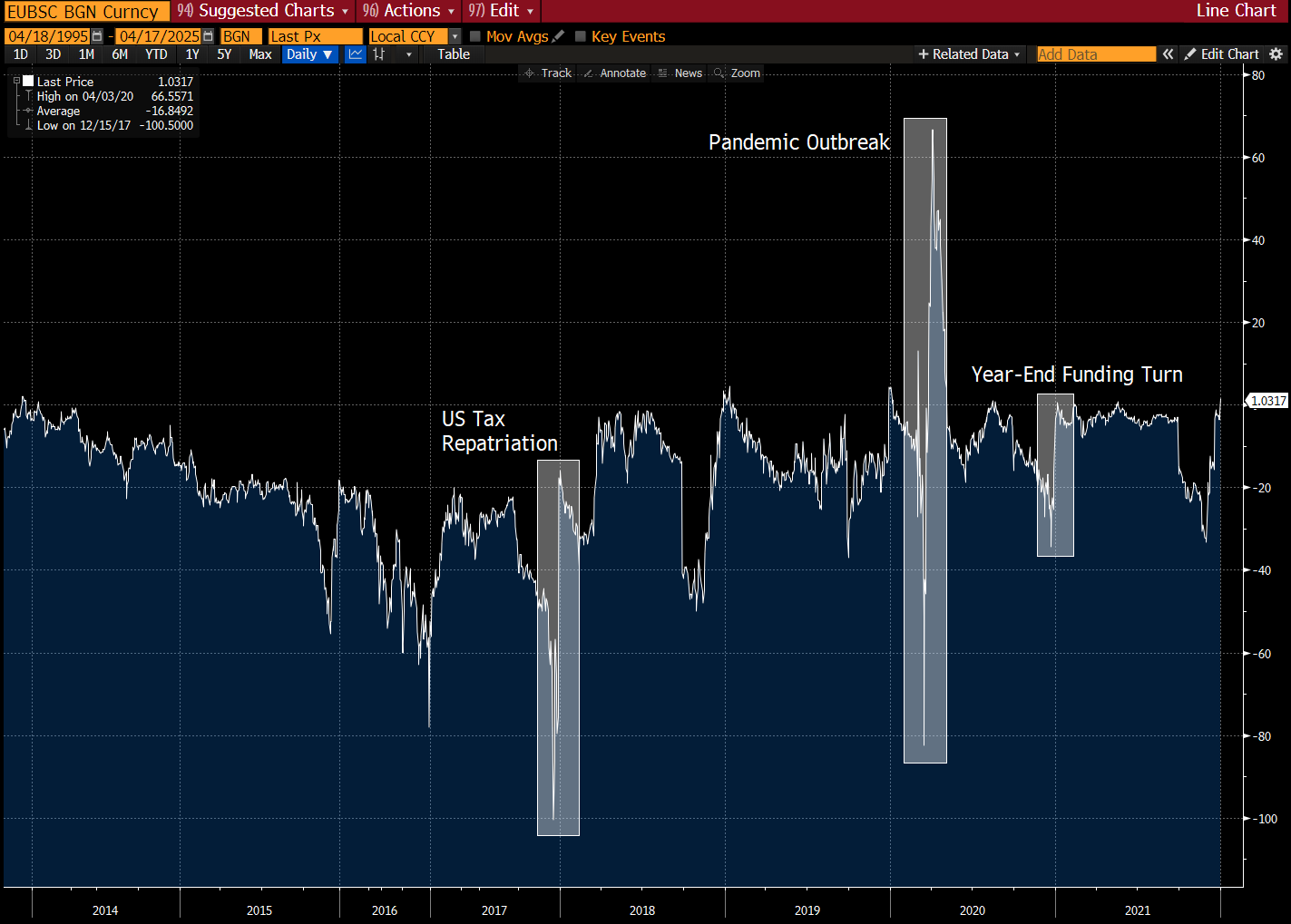

The cross-currency basis is rarely zero and fluctuates based on various factors. To understand some of them, consider the following EUR/USD three-month basis spread showing some drivers of it over the years:

U.S. Tax Repatriation:

In late 2017, there was a sharp blowout in the basis, with it trading down to -100bps before rallying back. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (passed in December 2017) allowed U.S. multinationals to repatriate overseas earnings at a lower tax rate. This reduced the incentive to hold USD-denominated assets offshore, leading to a pullback in USD supply from foreign affiliates of U.S. corporates. As a result, non-US banks had a harder time sourcing USD in the short-term funding markets. This created a large premium for USD funding (i.e negative basis), but was something that was resolved swiftly.

Pandemic Outbreak:

There was a massive scramble for dollar liquidity as the COVID-19 crisis exploded into global financial markets in early 2020. As markets tanked in early 2020, there was enormous demand for dollar funding for basically everything. This included covering margin calls, repaying USD-denominated debt, hedging dollar exposures and more.

The basis traded so low that on March 15 and again on March 19, 2020, the Fed reactivated and expanded its swap lines with major central banks. Foreign central bank swap-line borrowing surged. As the below chart shows, swaps went from basically zero to $160 billion on March 19, reaching nearly $450 billion by the end of April:

Year-End Funding Turn:

We flagged up the turn in 2020, but you can equally see it pronounced in several other years. There is a well-known seasonal pattern in global funding markets, where you tend to see increased demand for USD liquidity into year-end.

Part of this relates to balance sheet constraints for dealers, where they reduce risk around year-end to shrink their balance sheets and avoid regulatory capital charges. Banks, in general, look to window dress their balance sheets for regulatory disclosures at year-end, which means they offload risky assets, curtail USD lending, and cut swap exposures. This reduces the supply of USD in FX swap and cross-currency swap markets, making the basis more negative.

On the other hand, non-U.S. banks, along with asset managers and corporates, often need to settle USD liabilities or rebalance books at year-end, creating higher demand for USD and putting the basis lower.

This typically reverses in early January, which is why you can see the swift reversal on the chart.

When we look to summarise the drivers, dollar funding stress is typically the main driver behind large basis swings. Interest rate differentials has a more theoretical impact, with central bank interventions also something to have in mind.

Liquidity and Market Structure

The cross-currency basis market has evolved significantly over the past two decades, with a well-developed and active OTC market extending across the curve, not just in the front-end, but also in intermediate and long-dated maturities, in some cases out to 30 years. These longer-dated swaps are particularly relevant for insurers, pension funds, and corporates managing structural currency exposures on multi-year horizons.

While the majority of trades are still booked over-the-counter (OTC), the appeal of this space lies in the bespoke nature of the contracts. Dealers and clients negotiate specific terms (notional amounts, tenors, currency pairs, reset conventions, and collateral arrangements), making the OTC format well-suited to tailored hedging and funding strategies.

Liquidity is deep in the shorter end of the curve, especially in the 1-month, 3-month, and 1-year tenors for major pairs such as EUR/USD and USD/JPY. While long-dated swaps are widely traded and essential for many institutions, liquidity in times of stress or outside of core currency pairs can pose mark-to-market challenges and wider bid-ask spreads.

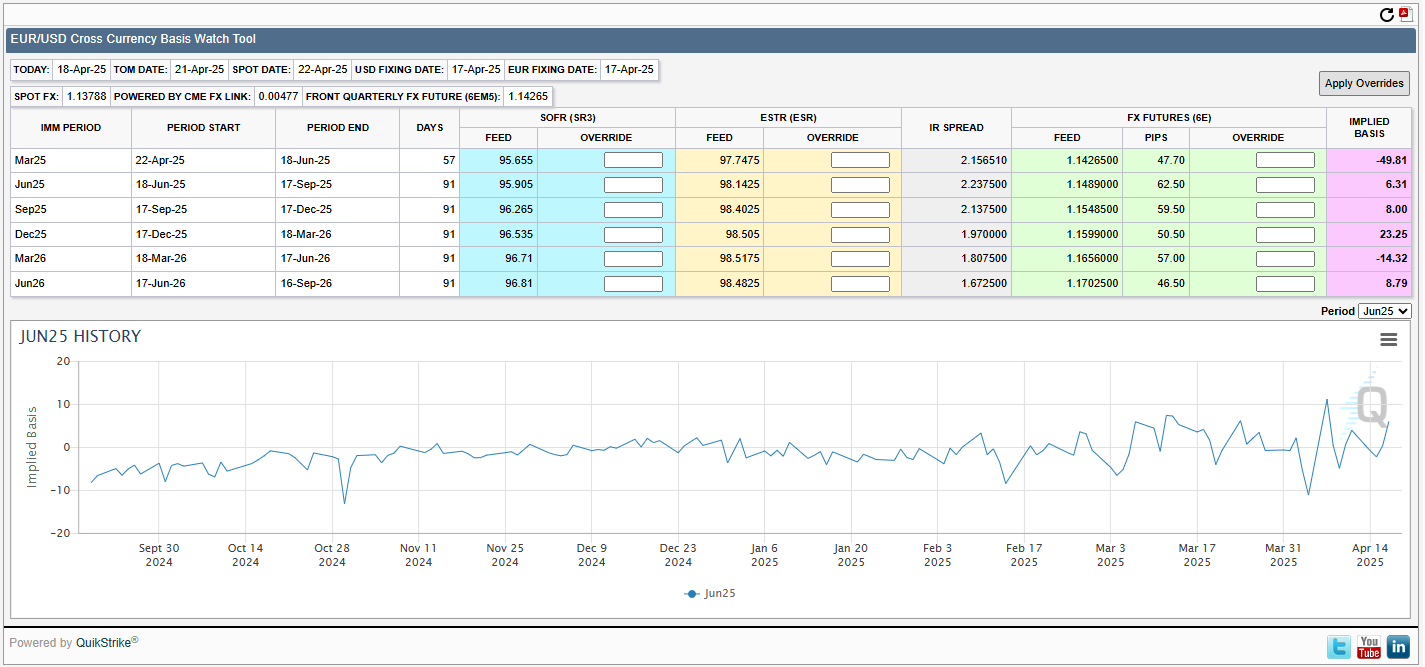

Advancements in the market mean that you can book and trade exposure on an exchange. In February 2025, CME Group launched EUR/USD Cross-Currency Basis Futures, a cash-settled contract designed as a transparent and cost-effective tool for trading cross-currency basis exposure.

These futures target the 3-month IMM-dated EUR/USD basis and settle against the CME EUR/USD Cross-Currency Basis Index, calculated daily using prices from SOFR futures, ESTR futures, and EUR/USD FX futures.

These futures offer significant advantages compared to the OTC market. OTC XCCY basis swaps involve physical principal exchanges, bilateral negotiations, and varying credit support annexes, leading to opacity and higher costs from counterparty risk and operational complexity.

In contrast, futures are standardised, centrally cleared, and traded on a transparent exchange, reducing risk and enhancing price discovery through the central limit order book (CLOB). Their cash-settled nature eliminates the need for principal exchanges or managing mandatory break clauses, lowering transaction costs and simplifying execution. By streamlining exposure to the EUR/USD basis without requiring separate FX or interest rate swap bookings, these futures provide a more efficient tool for hedging and speculation.

CME also offer a basis watch tool, whereby those without easy access to a Terminal can easily see the implied basis for different contracts:

Despite the advancements in the swap market, any counterparty that needs to book a bespoke deal will still go to the OTC space, and that’s unlikely to change anytime soon.

Trading Strategies in Cross-Currency Basis Markets

To be clear, hedging activity dominates the swap market, especially in terms of notional volume. However, hedge funds and prop desks can and do speculate using the products, with three main ways:

Basis Arbitrage

Let’s say you’re on a prop desk and are tracking the EUR/USD forward curve, the current SOFR and EURIBOR 3-month rates, and the cross-currency basis spread. You might notice that the negative basis on EUR/USD is kicking out, but the forward curve doesn’t match this move.

In this example scenario, the 3-month contract is -80bps, which you feel is excessive, given that it has deviated significantly from covered interest parity (CIP) and the theoretical FX forward pricing.

In this case, if you could borrow USD close to SOFR, you could enter a XCCY 3-month swap on EUR/USD. On the swap, you’d buy EUR and sell USD.

You’d pay the interest at X% on the EUR borrowings but receive USD funding plus the extra on top as the basis (+80bps). Then at the end of the swap, you’d get back the USD and pay it back.

In theory, if there were an arbitrage opportunity here, you would capture it via the difference in the implied cost of USD funding versus the actual cost of funding from the basis swap.

In the real world, exploiting mismatches between FX forward rates and interest rate differentials by using cross-currency basis swaps is difficult. Usually, we’re talking just a few basis points of difference, with large nationals and leverage needed to profit from this trade meaningfully.

Relative Value Trading

This can be thought of as similar to trading curve flatteners or steepeners on sovereign bond yield curves.

Example: A trader might look at the EUR/USD on a one-year basis relative to the five-year basis. Suppose the one-year basis is –10bps, while the five-year is –30bps. If the trader expects this spread to flatten (i.e. the five-year becomes less negative relative to the one-year), they could take a non-directional trade purely trying to exploit the basis movement. In this case, they would receive on the one-year basis and pay on the five-year basis. Then, if the curve flattens (for example, the one-year moves to –15bps and the five-year moves to –20bps), the trade would be profitable.

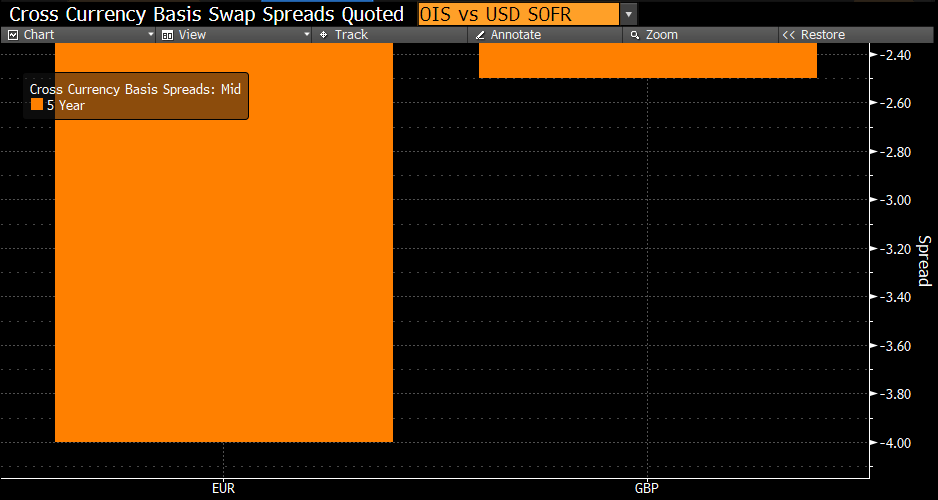

You can also trade the basis between different currency pairs using a relative value strategy. For example, the five-year EUR/USD basis currently sits at –4 basis points, while the GBP/USD basis is at –2.5 basis points. If you believe this relationship is mispriced, you can express a view by entering a spread trade between the two. Specifically, if you expect the EUR/USD basis to widen further (i.e., become more negative) relative to GBP/USD, you would receive the EUR/USD basis and pay the GBP/USD basis. If the EUR/USD basis moves from –4bps to –6bps while the GBP/USD basis holds steady, the trade would generate a profit, as the widening EUR/USD leg works in your favour and the GBP/USD leg remains stable.

Macro & Central Bank Policy Plays:

Normally, such plays would often be traded on the currencies outright or via rate futures contracts. However, cross-currency basis swaps can also be used.It does present a clean way to express a view if you believe central bank intervention to boost liquidity is coming, such as during the pandemic. In that case, a view that the Fed would step in to ease USD funding pressures would typically be expressed by paying the basis on the non-USD leg (i.e. receiving USD basis), anticipating that the basis would tighten (become less negative) as dollar liquidity improves.

Conversely, if a trader expects market uncertainty or a surge in demand for USD funding, leading to a wider, more negative basis, they could express this by receiving the basis on the non-USD leg (i.e. paying USD basis), positioning for further USD scarcity.

Framing trades relative to the non-USD leg is the market convention, and helps ensure clarity when discussing directional views on the basis.

Behavioural Aspects and Market Psychology

As in STIR markets, cross-currency basis trading is subject to behavioural biases and market inefficiencies. Below are three we wanted to flag:

Herd Mentality:

During funding crises, traders rush to secure USD liquidity, amplifying moves in the basis. We spoke about this earlier when talking about the pandemic rush in 2020. Corporations, banks and asset managers rushed to obtain dollars to cover margin calls, redeem debt, and secure short-term liquidity. The basis blew out massively beyond what interest rate differentials would suggest, and was simply a stampede of the herd.

The year-end funding turn also turns into a herd mentality bias, as it’s a recurring event. Market participants expect this, and begin pre-emptively rushing to secure USD funding in the basis swap market. Swaps often widen sharply in the weeks before year-end, even if real demand doesn’t justify it.

Overreaction to Policy Announcements:

Market participants may overprice expected central bank actions, creating mean-reverting opportunities. This is something that’s not unique to this market, but rather can be seen in almost all asset classes.

However, the overreaction can be noted because the combination of the swap pricing in line with FX and IR implied differentials means that market fear or greed becomes apparent via arbitrage.

Given the lack of liquidity in some currency pairs and tenors (given the OTC pricing), the overreaction can become even more pronounced in the short term.

Recency Bias:

Recency bias in this market leads investors and traders to anchor spread movements on the most recent basis, assuming that the recent widening/tightening will continue. This serves as a blind bias because part of the price action in this market is based on longer-term trends or macro fundamentals.

The year-end seasonal turn is a classic case, with traders front-running expected moves earlier each year, widening the spread sooner and potentially overshooting. Some hedge in anticipation, even if their actual USD needs are minimal, simply because “it happened last year.”

Conclusion

Cross-currency basis trading sits at the intersection of global funding, interest rate policy, and FX risk management. What may seem like a niche segment of the derivatives market is, in fact, a crucial mechanism underpinning global capital flows. It facilitates borrowing across currencies, enables FX-hedged investment strategies, and acts as a release valve when dollar liquidity tightens, whether due to policy shifts, macro shocks, or regulatory constraints.

While most of the market’s volume is driven by hedging needs—corporates funding overseas operations, insurers and pension funds aligning currency exposures—there remains a thriving ecosystem of relative value and macro traders who monitor the basis for signs of dislocation. From exploiting deviations from covered interest parity to expressing views on central bank liquidity conditions, basis traders must blend quantitative discipline with macro instinct.

What makes the cross-currency basis market particularly compelling is its reflection of deeper structural forces. Regulatory pressures, balance sheet constraints, and monetary policy divergence have all distorted what used to be a clean arbitrage relationship. The basis is no longer just a passive pricing element; it’s a signal of global stress, a cost of capital, and a trading opportunity all at once.

As the market continues to evolve (especially with the rise of centrally cleared futures, expanded swap lines, and a maturing RFR environment), traders and institutions will need to adapt. But the core challenge remains the same: managing liquidity and risk across borders, in a world where funding is never truly frictionless.

In that sense, mastering the cross-currency basis isn’t just about pricing a swap. It’s about understanding the structure of global finance—its incentives, imbalances, and behaviour under pressure.

We hope you found this primer helpful. As always, likes and comments are appreciated. Let us know what topics you’d like covered next.

SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) for USD / EURIBOR (Euro Interbank Offered Rate) for EUR / TONAR (Tokyo Overnight Average Rate) for JPY / SONIA, SARON, and other RFRs for GBP, CHF, etc.

Great write up.

Apart from the recent CME tools, how do you monitor the xccy basis if you don’t have a Bloomberg?

This is a super article! Thank you for sharing