For all the attention that stock markets and interest rates get, the real heartbeat of the global financial system ticks quietly in the background: the repo market.

Short for repurchase agreements, repos are short-term secured loans that underpin daily funding flows across the global financial system. Banks, dealers, money market funds, hedge funds, and insurers all rely on repos to borrow or lend cash against high-quality collateral, typically government bonds. It’s the mechanism that keeps liquidity circulating. Without it, credit markets would seize, central banks would lose control over short-term rates, and liquidity mismatches would surface across everything from derivatives desks to corporate treasuries.

Most of the time, the repo market operates quietly in the background, invisible to most. But in moments of stress (like the “repocalypse” of September 2019 or the crunch of March 2020), it becomes the centre of gravity. When repo markets break, the rest of the system feels it fast.

This primer runs through:

- Repo market basics (mechanics and visualisation)

- Why collateral is everything

- Repo’s role in monetary policy and liquidity transmission

- Historical stress events and market fragility

- Key participants in the ecosystem

- Trading strategies, from balance sheet engineering to funding arbitrage

(If you like FX basis, STIRs, or balance sheet plumbing, you’ll feel right at home. If you don’t, grab a coffee and read it twice. This is the machinery behind the curtain.)

Note: When we refer to the “repo rate”, we’re generally referencing the overnight General Collateral (GC) rate on U.S. Treasury collateral. Bloomberg ticker: USRG1T.

Understanding Repo Markets

At its core, a repurchase agreement (or repo) is a short-term collateralised loan. One party sells securities (typically government bonds) to another, with an agreement to buy them back later at a slightly higher price.

There are two legs to every repo transaction:

- Initial Sale: The seller delivers securities and receives cash.

- Repurchase: The buyer returns the securities and is repaid with a small interest payment, known as the repo rate.

From the cash lender’s perspective, the repo is a secured loan. From the borrower’s side, it’s short-term funding backed by liquid, high-quality collateral.

Repo transactions can be structured in various tenors. The most common are overnight, but term repos and open repos1 are also widely used. These agreements sit across a layered architecture—tri-party, interdealer, and bilateral—each with its own operational structures and risk conventions.

Basic Mechanics

Example: A dealer facing month-end balance sheet constraints enters an overnight repo. To manage its leverage ratio, the dealer pledges $1 billion of US Treasuries as collateral and borrows cash at the GC rate. The next morning, the dealer repurchases the securities at a slightly higher price, having secured short-term funding while temporarily reducing balance sheet usage.

Repo Seller (Borrower):

- Needs $X million in cash overnight.

- Sells $1 billion of Treasuries into the repo market.

- Agrees to repurchase the Treasuries the next day at a pre-agreed price (original notional + accrued interest).

- The implied interest, when annualised, reflects the repo rate.

Example: A corporate treasury team managing excess liquidity allocates capital into overnight repos to preserve flexibility while earning a secured return. The company lends cash to the market and receives US Treasuries as collateral, which are returned the following day.

Repo Buyer (Lender/Reverse Repo):

- Has $1 billion in excess liquidity.

- Lends into the repo market and receives Treasuries as collateral.

- Sells the Treasuries back the next day and is repaid the original cash plus interest.

- The implied interest, annualised, gives the repo rate.

In both cases, collateral is assumed to be US Treasuries. In practice, repo rates vary depending on the quality and scarcity of collateral, the tenor of the trade, and market liquidity conditions.

Repo Markets Visualised

Our good friend Conks is well known for his infographics, with the below providing a great in-depth view of repo market participants and trade flow routes in the repo space:

Repo Rates Versus Other Types

Understanding how repo rates compare to other short-term interest rates is critical for interpreting funding dynamics. The secured nature of repos sets them apart from unsecured lending rates and gives rise to different benchmarks with varying market relevance.

Fed Funds

The federal funds rate is the benchmark for unsecured overnight lending between US depository institutions. It represents the rate at which banks with surplus reserves lend to banks facing shortfalls, typically on an overnight basis.

By contrast, repo transactions are secured by collateral, most often in the form of US Treasuries. This collateralisation significantly reduces counterparty risk, which is why repo rates tend to price below unsecured benchmarks in times of stability.

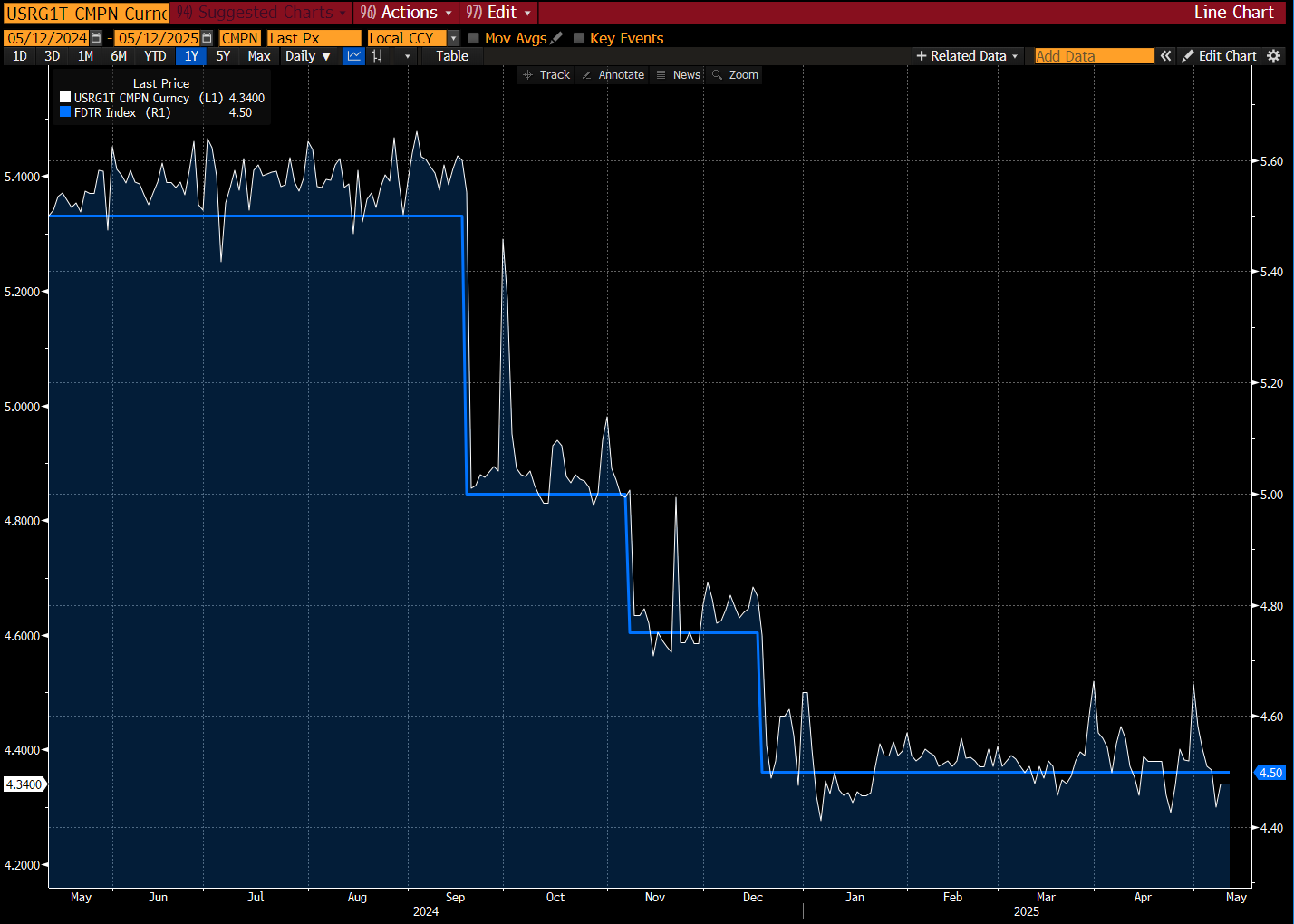

While the federal funds target range is set by the Federal Reserve, the effective fed funds rate (EFFR) floats within that corridor and reflects actual transactions. The secured GC repo rate (USRG1T) tracks differently, anchored by the value of collateral and broader liquidity conditions in the Treasury market.

In short, repo markets reflect the cost of secured overnight liquidity. Fed funds reflect unsecured interbank trust. The gap between the two becomes especially telling during stress events or regulatory year-end effects.

SOFR

The Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) is conceptually closer to the GC repo rate. Both are benchmarks for secured overnight borrowing using Treasury collateral. However, there are key differences.

SOFR is calculated and published by the New York Fed once daily, based on a volume-weighted median of overnight repo transactions across a broad segment of the market, including bilateral and tri-party trades. It is designed as a comprehensive, stable benchmark to replace LIBOR.

The GC repo rate (USRG1T), on the other hand, reflects live, tradeable quotes in the dealer market—updated throughout the day and directly observable on Bloomberg terminals. It represents where cash actually clears in the interdealer tri-party market at any given time.

While SOFR and GC repo typically trade in close alignment, divergences can appear during quarter-ends or episodes of funding strain, where GC repo may spike while SOFR remains more stable due to its averaging methodology.

Think of SOFR as a backwards-looking composite, while GC repo prints live at the point of execution. Both reflect secured funding, but one is a benchmark; the other is a market rate.

Bilateral vs Tri-party Repo

The structure of a repo transaction (whether bilateral or tri-party) shapes everything from margining conventions to the interest rate paid.

Bilateral repo involves a direct agreement between two counterparties. Terms are negotiated on a deal-by-deal basis, allowing for greater flexibility in collateral type, haircut, and maturity. However, this flexibility comes with increased operational and counterparty risk, as each trade must be separately managed and settled.

Tri-party repo, by contrast, introduces a third-party clearing agent (typically BNY) to manage collateral selection, valuation, margining, and settlement. This model dominates the general collateral (GC) space due to its efficiency, scale, and automation.

In normal conditions, tri-party repo typically clears at tighter spreads (lower funding costs) than bilateral repo. This is driven by operational streamlining, deeper liquidity, and the netting benefits of large dealer platforms.

However, when specific collateral is needed, such as a particular off-the-run Treasury, bilateral trades become dominant. These so-called “specials” carry a lower implied yield for the lender and a higher funding cost for the borrower, as participants compete to borrow the same issue.

Put simply, general collateral lives in tri-party. Special collateral lives in bilateral. And the cost of funding adjusts accordingly.

Collateral in Repo Markets

If there’s one concept that sits at the heart of repo pricing, it’s collateral.

In theory, repos are about funding. In practice, they’re about collateral—its quality, availability, and desirability. The type of collateral pledged in a repo not only determines the interest rate but also shapes how trades clear, how risk is managed, and where stress emerges.

Typical Collateral

The repo market runs on a collateral hierarchy.

At the top are government bonds: US Treasuries, German Bunds, and UK Gilts. These are the most liquid and lowest-risk assets available in global markets. If a borrower defaults, these securities can be sold with minimal friction, which is why they attract the tightest repo spreads and lowest haircuts. They’re the closest thing to money without being money.

Next are agency securities, issued by US government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These instruments carry either implicit or explicit government backing, making them broadly acceptable as repo collateral, but with slightly wider spreads and higher haircuts than Treasuries. Their liquidity profile is strong, but not bulletproof.

Further down the stack are investment-grade corporate bonds. These can be repo’d, but usage is less common and much more selective. The credit risk is idiosyncratic, and the market liquidity is thinner. As a result, haircuts are wider, spreads are higher, and each trade tends to be bespoke.

Collateral eligibility and pricing are always a function of risk appetite, regulation, and market conditions, but this broad hierarchy remains intact across jurisdictions.

The Scarcity Factor

Not all collateral is equal. But sometimes, even among equals, one bond becomes more valuable than the rest.

This is where the concept of a “special” comes in. In repo terms, a bond goes “on special” when demand to borrow it overwhelms supply. This drives its repo rate below the GC rate, sometimes dramatically so.

A negative repo rate means the lender is effectively paying to lend the bond. Why would they do that? Because the borrower needs it badly enough to make it worthwhile, typically to cover a short, meet delivery obligations, or hedge a derivative.

The most common driver of specials is short positioning. If a hedge fund is short the 10-year Treasury future, for example, it may need to borrow the corresponding on-the-run 10-year note to deliver into settlement. When many funds crowd into the same trade, the pressure on that specific bond builds, and the repo rate collapses.

Example: March 2021. The most recently issued 10-year US Treasury note went sharply negative in repo. Hedge funds, betting on higher yields and higher inflation, had built significant short positions. To maintain those positions, they needed to borrow bonds. But quarter-end balance sheet constraints limited supply. Dealers, unwilling to lend freely, withheld inventory, tightening the squeeze. At the extreme, repo lenders were paying borrowers just to get access to the bond.

This dynamic made it more expensive to run short positions and signalled tension in the plumbing, despite no broader credit stress. The specialness eased as market positioning normalised, but it underscored how critical collateral dynamics are to funding stability.

Collateral Terms

When a repo trade is booked, the lender doesn’t fund 100% of the collateral’s face value. Instead, they apply a haircut—a discount that protects against market moves and counterparty default.

The size of the haircut depends on collateral quality:

- US Treasuries (on-the-run): ~1.00-2.00%

- Agency MBS or GSE debt: ~1.00%–5.00%

- Investment-grade corporates: 3.00% and above

Haircuts are a crucial safeguard. If the borrower defaults, the lender needs a buffer to sell the collateral without incurring a loss. In times of market stress, haircuts can be raised, sometimes abruptly, forcing deleveraging and amplifying funding pressure.

Haircuts are also where repo intersects with regulation. Under Basel III, secured funding with high-quality collateral and low haircuts is treated favourably for capital and liquidity metrics. This has led to increased reliance on repo as a preferred form of bank funding.

Why Repo Markets Matter

Because retail investors don’t interact with the repo market, its importance is often overlooked. But make no mistake, this is the engine room of modern finance. Repo markets matter for three fundamental reasons:

Core Source of Short-Term Funding

Banks, dealers, and hedge funds depend on repo to fund bond inventories, deploy leverage, and manage day-to-day liquidity. For dealers, especially, repo enables financing of government securities positions without having to unwind them, preserving market liquidity and facilitating client flows.

It also allows institutions to optimise balance sheet usage. Under Basel III and similar regulatory frameworks, secured funding is treated more favourably than unsecured borrowing. Repo markets, particularly those backed by high-quality collateral, offer balance sheet-efficient access to liquidity.

In normal conditions, repo is deep, liquid, and relatively low-risk. But its role becomes even more vital during periods of stress, when unsecured markets freeze, repo often remains the last functioning funding route.

Anchor for Monetary Policy

Repo markets are one of the primary levers through which central banks transmit monetary policy.

Take the Fed’s policy corridor as an example: by conducting repo operations (injecting liquidity) or reverse repo operations (withdrawing liquidity), the Fed nudges overnight market rates toward its target range.

- In a liquidity squeeze, repos provide reserves, lowering short-term rates.

- In a glut, reverse repos soak up excess cash, lifting rates back toward target.

Repo operations also serve as signalling tools. Adjustments in size, frequency, eligible collateral, or counterparty access can all communicate policy direction. And because repo rates influence a wide swath of short-term funding costs—from bank liabilities to commercial paper—they indirectly shape borrowing costs across the economy.

In effect, the repo rate doesn’t just track monetary policy. It helps enforce it.

Leading Indicator of Financial Stress

The repo market reflects the real-time price of cash and collateral. When tensions build—whether due to liquidity mismatches, balance sheet constraints, or collateral hoarding—repo rates move first.

- A sudden spike in GC repo can signal systemic funding stress.

- A deeply negative special rate might indicate positioning imbalances or collateral scarcity.

- A persistent divergence from central bank target rates suggests a breakdown in transmission.

Repo dislocations are often the canary in the coal mine. In 2008, the withdrawal of repo funding preceded institutional failures. In September 2019, the Fed was forced to re-enter the market as GC rates spiked above 8%. In March 2020, even Treasury repo markets buckled under the strain.

When the repo market breaks, it’s not just a footnote, but often the first crack in the dam.

Notable Stress Events

While the repo market typically operates quietly in the background, it has been a central point of stress in several major financial episodes. Below are three examples where dislocations in repo funding revealed broader fragilities across markets.

September 2019

In September 2019, U.S. overnight repo rates experienced a sudden and sharp spike, from around 2% to over 6% in a single day. Some trades even cleared at higher levels intraday.

The dislocation was driven by a temporary shortfall in cash. A combination of corporate tax payments and large Treasury settlement flows drained reserves from the banking system. At the same time, balance sheet constraints prevented large institutions from stepping in to lend.

The Federal Reserve responded by launching a series of repo operations to restore liquidity. These injections calmed the market quickly, but the episode highlighted how little excess capacity existed in the post-crisis funding system. It also prompted a broader rethink of how reserve levels interact with repo market functioning.

Global Financial Crisis (2008–2009)

During the 2008 financial crisis, stresses in the repo market emerged well before the collapse of major institutions. As concerns about credit risk escalated, repo counterparties began demanding higher haircuts, particularly for lower-quality collateral such as mortgage-backed securities, or refusing to roll repo lines altogether.

Institutions like Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, which relied heavily on short-term repo funding to finance large securities inventories, found themselves unable to secure liquidity. The pullback in repo availability contributed to their rapid deterioration.

This episode underscored the repo market’s role as a transmission channel for systemic risk, especially when counterparties become unwilling to accept anything but the highest quality collateral.

March 2020

At the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, the US Treasury market—typically the most liquid in the world—experienced significant stress as investors rushed to raise cash. As Treasury securities were sold en masse, repo markets also came under pressure.

Market participants faced difficulty sourcing funding for even the most liquid collateral. Dislocations appeared in both general collateral and specials markets, and some firms were forced to unwind positions due to tighter margin conditions.

In response, the Federal Reserve reintroduced large-scale repo operations alongside a broader suite of liquidity measures. These efforts helped stabilise short-term funding markets and restore confidence in Treasury market functioning.

Key Participants in Repo Markets

The repo market brings together a wide range of participants, each with distinct roles depending on their funding needs, investment objectives, and access to infrastructure. While banks and non-bank financial institutions dominate in terms of daily activity, central banks play an outsized role in shaping the structure and pricing of the market.

- Banks and broker-dealers are the primary liquidity providers in the repo market. Dealers use repos to fund inventories of government securities, manage balance sheet liquidity, and intermediate between cash providers and borrowers. These desks often sit within broader short-term interest rate trading (STIRT) teams or as part of financing units under fixed income, currencies, and commodities (FICC) divisions.

In tri-party and bilateral repo markets, dealers act as both counterparties and facilitators. On the borrowing side, they finance their own positions or source collateral for client trades. On the lending side, they provide access to repo for institutional cash investors, often matching flows across books to run “matched repo” operations that generate spread income.

- Hedge funds are also active repo borrowers. They use repos primarily to obtain leverage for directional or relative value strategies, particularly in government bond markets. For example, hedge funds executing basis or curve trades often rely on repo financing to take on large bond positions while minimising capital deployment.

Because repo transactions are collateralised, they typically offer hedge funds a cheaper form of leverage than unsecured borrowing or derivatives margin funding. This makes repo a central component in leveraged fixed-income strategies.

- Money market funds (MMFs) are among the largest repo lenders. These funds seek secure, short-term investments, and repos meet both their liquidity and credit quality requirements.

MMFs routinely provide cash to dealers in the tri-party market, receiving high-quality collateral in exchange. This function supports market liquidity and provides a key funding channel for primary dealers.

- Central banks participate in repo markets to implement monetary policy, not to meet funding needs. Through repo and reverse repo operations, central banks manage short-term interest rates and influence liquidity conditions.

Facilities like the Federal Reserve’s Overnight Reverse Repo Program (ON RRP) allow eligible counterparties—primarily MMFs, government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), and banks—to invest surplus cash securely at the administered rate, which acts as a floor for overnight rates. Conversely, standing repo facilities (SRF) allow banks and dealers to obtain liquidity against government collateral, acting as a ceiling on funding costs.

These operations help central banks steer money market rates within their policy corridors and ensure orderly market functioning during periods of stress.

- Large corporates with substantial cash holdings may access repo markets indirectly, typically via banks or investment in money market funds. While they are not major drivers of daily activity, corporate treasurers occasionally use repo to enhance returns on idle cash while preserving overnight liquidity.

This type of participation is more opportunistic and is generally limited to the most creditworthy counterparties and highly standardised repo structures.

Speculation in Repo Markets

While the repo market is primarily transactional—serving the day-to-day funding and liquidity needs of banks, funds, and dealers—there are instances where it facilitates sophisticated trading strategies. These cases are relatively niche and often involve exploiting dislocations in funding rates or market structure.

Specials Trading

When a specific bond becomes scarce in the market, often due to heavy short interest or its status as a benchmark issue, it may trade at a “special” repo rate, meaning it clears well below the GC rate. This dynamic creates opportunities for repo desks and traders with access to that security.

Example: A trader anticipates that a newly auctioned Treasury note will become “special” due to elevated short demand or benchmark index inclusion. They acquire the bond in the cash market and simultaneously lend it out via a repo agreement. If demand rises and the repo rate on that specific bond falls, the trader benefits from the spread between GC funding and the now-lower special rate, effectively earning a premium for supplying the scarce collateral.

This approach does not involve directional risk on rates or prices. It is purely an attempt to monetise the collateral premium embedded in specials pricing.

Basis Trading

Repo markets also play a supporting role in basis trades, where traders arbitrage the price difference between a cash bond and its corresponding futures contract. This typically involves buying the underlying bond and selling the futures contract short.

To execute the bond leg, traders need to fund the purchase, often done through repo. The repo provides efficient, secured financing and reduces the cost of carry, which is a key component in determining the profitability of the trade.

The repo rate directly impacts the implied basis and can influence trade entry levels. While the strategy itself is not about the repo market per se, successful execution often depends on reliable access to repo funding at known rates.

Conclusion

Repo markets form the foundation of modern market liquidity. They enable institutions to finance positions, manage balance sheets, and transmit monetary policy efficiently. When functioning normally, the system remains largely invisible, facilitating trillions in daily flows with little disruption. But when cracks appear, the effects are felt quickly and broadly, exposing just how critical this market really is.

Whether through stress events, dislocations in collateral, or subtle shifts in repo rate dynamics, the repo market offers a real-time lens into the financial system’s liquidity conditions. For those involved in trading, risk management, or macroeconomic strategy, understanding repo is not optional—it’s foundational.

We hope you enjoyed this primer and insights on repo markets. Please leave a like to show your support. As always, comments and opinions are welcome in the comments.

AP

Term repos = one week, one month, or longer. Open repos = rolled daily.

As someone who was a CEO of a $40 bn balance sheet Gov securities broker dealer, FICC full netting member and primary dealer, I can attest to this being a very clear and concise informative piece.

Very broad and clear. Gj !