The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The more you know, the more you realise you don't know.

Why do we fail to gauge our own abilities accurately? The human mind tends to overestimate this measure because it does not yet know enough to recognise its own incompetence.

According to one study, about 80% of people rate themselves as “above-average drivers,” an assumption that is most probably incorrect. Another study showed that 42% of employees surveyed at a high-tech software engineering company assessed their own performance as being in the top 5%. Of course, this is (once again) likely an inaccurate self-observation.

This lack of awareness can cause a person to feel unjustifiably confident—which is often the hallmark of the Dunning-Kruger effect.

What is this bias?

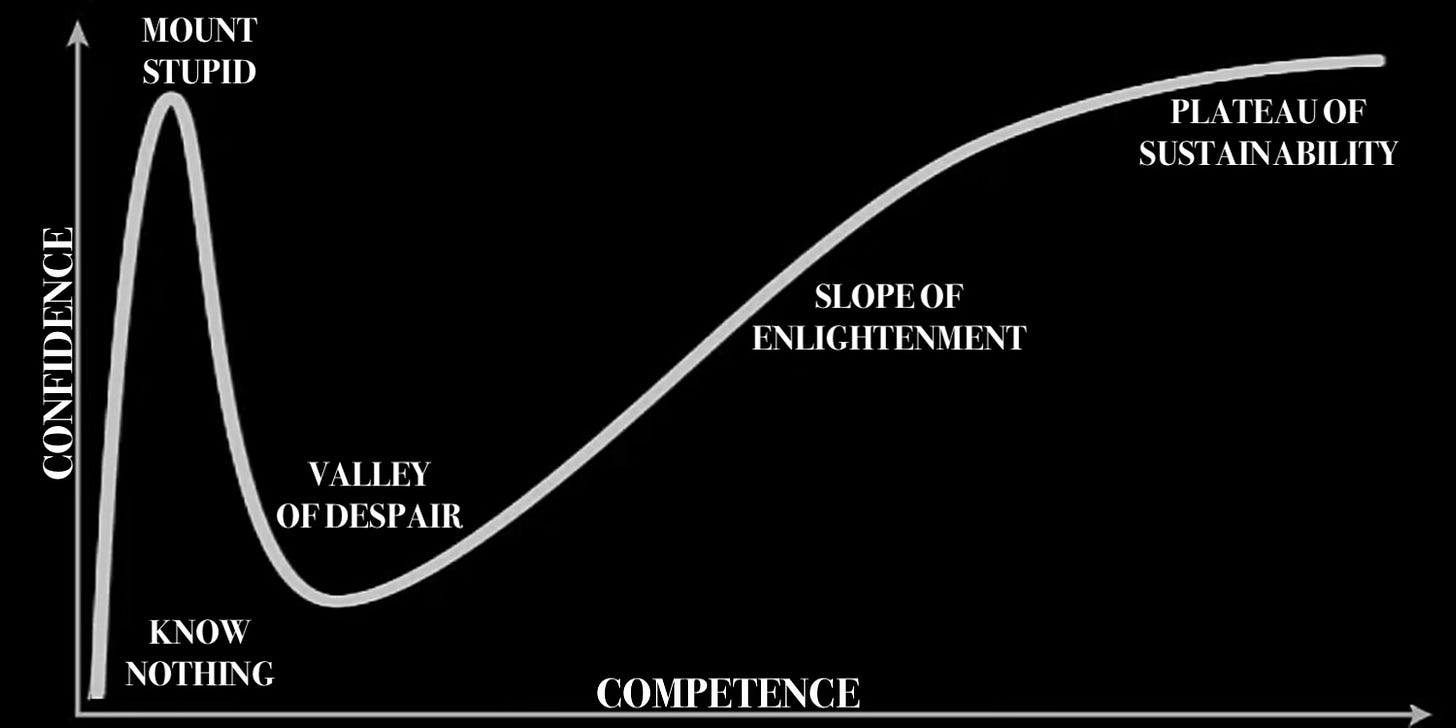

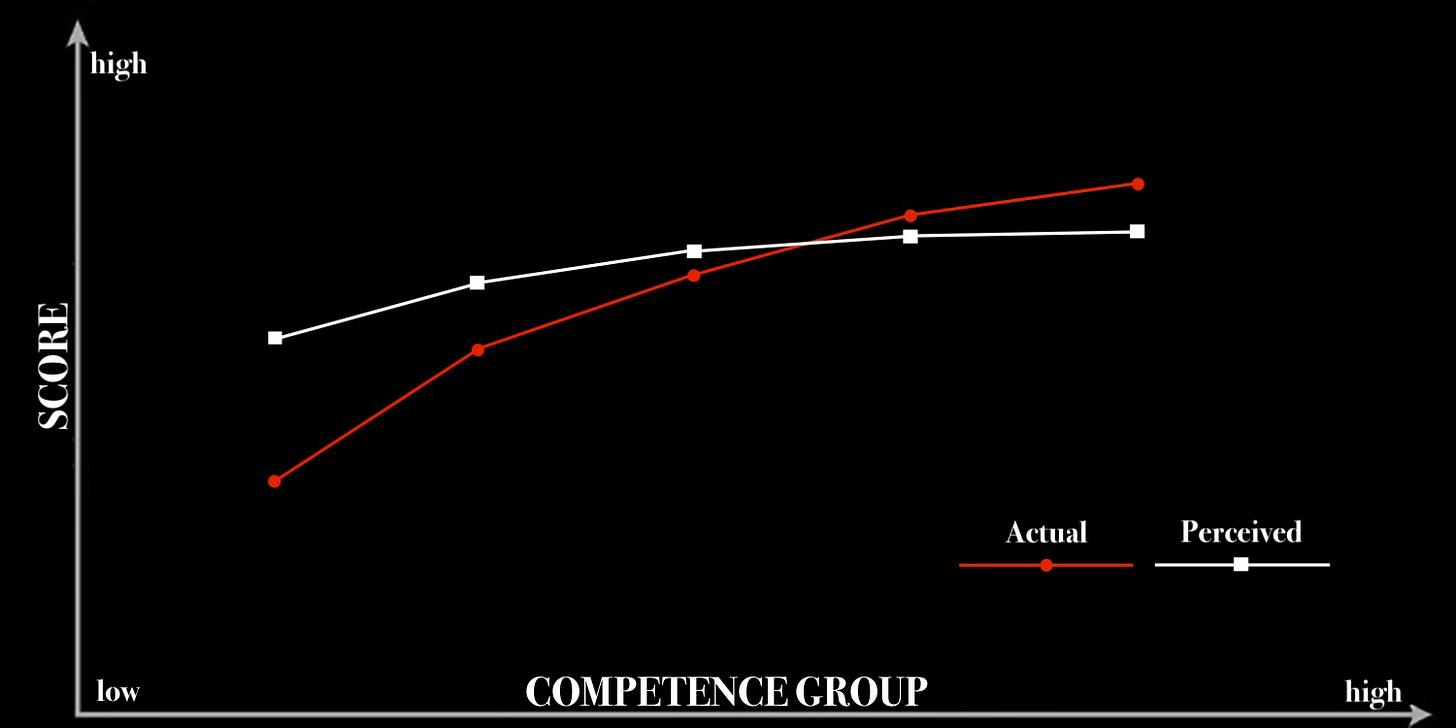

The Dunning-Kruger effect refers to the phenomenon wherein individuals with limited knowledge and skill in a particular area tend to overestimate their own proficiency. By contrast, this effect also leads highly competent individuals to perceive tasks within their domain as straightforward for everyone, thereby causing them to underestimate their own abilities.

In our behavioural finance series, we look at how these biases affect traders and investors when it comes to making decisions and taking on risk. The Dunning-Kruger Effect can exert a significant influence on financial decision-making and investment strategies. Novice investors are prone to overestimating their capacity to select stocks, evaluate companies, or forecast market trends, resulting in suboptimal investment decisions and potential financial setbacks. This phenomenon encompasses a failure to identify unrecognised risks that may be inherent in the investment landscape.

There are often many links between trading and poker (it’s worth taking a read of a recent article on this: “Trading Lessons From Poker”). Both require placing bets on incomplete information. The Dunning-Kruger effect poses a particularly significant challenge for poker players due to the game’s inherent element of chance, which diminishes the clarity of causal relationships between actions and outcomes. This creates an environment in which the Dunning-Kruger effect can wreak havoc. The randomness can reinforce bad behaviours and punish good behaviours in the short term. In the long term, it also makes it tougher to correct course because it’s not obvious what’s right from wrong.

If you think you have never succumbed to Dunning-Kruger, let us ask you this: Have you ever been at a loss for what to study next? Many individuals, including poker players, may mistakenly believe they have reached a pinnacle of mastery when they encounter a lack of direction in their learning. This situation arises from limited exposure to learning experiences, which in turn hinders the recognition of one’s own ignorance. As knowledge expands, so does the awareness of its limitations, revealing the vast expanse of the unknown beyond our current understanding.

“The more you know, the more you realise you don’t know.” — Aristotle.

How to overcome the bias

How are those who underperform supposed to see their own lack of ability when it takes the ability to see one’s lack of ability to be aware of it? It’s the awareness that is crucial to overcome a lack of ability.

You can avoid being ignorant of your own performance by listening and gaining insight into the performances of others. Having a diversification of perspectives plays an important role.

Recognising your own limitations and being open to feedback and constructive criticism are also contributing factors to overcoming this bias.

Remember, you’re not the smartest person in the room. And if you are, then you’re in the wrong room.

(…or, at least, that’s what your Dunning-Kruger-affected brain will tell you)

If you enjoyed this article, please do us a huge favour by simply clicking the like button. Feedback through engagement is an indication and driver for us to work from.

Have a great week.